![[RSS]](/static/img/feed-icon-14x14.2168a573d0d4.png) Conservancy Blog

Conservancy Blog

Cyborg Lawyer 2.0, "Hack Proof"

by on April 6, 2017

It's been quite a number of years since I got my first defibrillator/pacemaker and, a little bit earlier than expected[1], the battery is now starting to run out. While the alarm hasn't started going off yet (it's set to go off every day a little after noon once the power gets below the 30 day replacement threshold), it's down to the point that this can happen at any moment. There's no way to recharge the battery, though device manufacturers are working on that for future models, so it's surgery to take out the old one and implant a new one. Of course, I've known this was coming for a while, but for various reasons I wasn't that worried about it. I mean, after all, I still don't have access to the source code in my current defibrillator. I was expecting status quo, with the inconvenience of surgery and recovery but instead was faced with the possibility of something much worse.

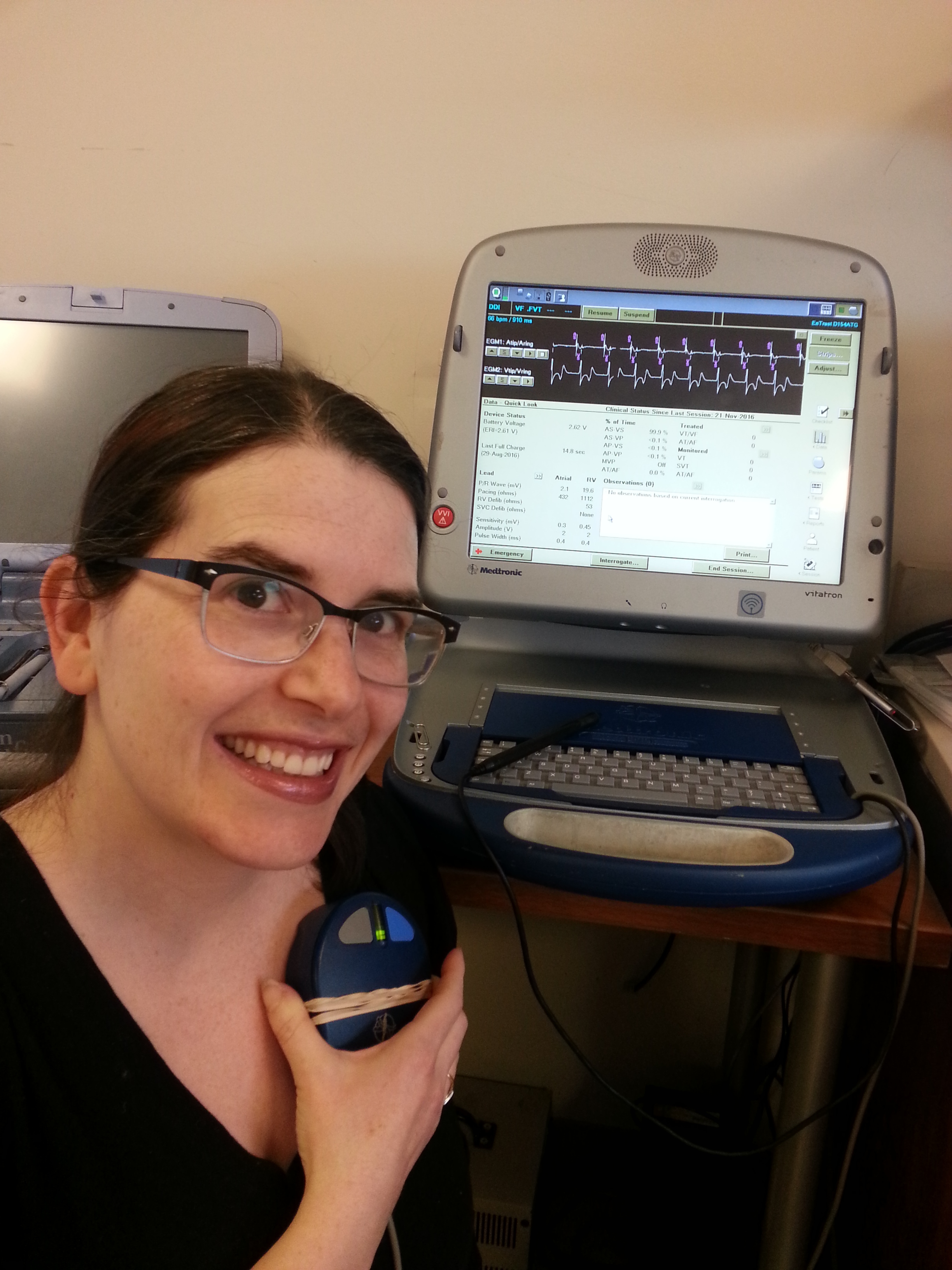

Karen getting her device interrogated via magnet

Back in 2007 when I first looked into getting my device, it was just before major research was published showing these devices to be vulnerable. I tried to convince my cardiologists and electrophysiologists that the issues around device security were critical, and that these device manufacturers got it backwards: no actual security but with proprietary software that cannot be reviewed or tested for safety. I explained that security through obscurity simply doesn't work. Initially, this did not go well at all but I finally found an electrophysiologist who got what I was saying [2]. He convinced me that I couldn't wait any longer to get the device and called around all of the local hospitals until he found one that had an old device that was still sterile. The older device had no wireless component, and could only be communicated with via a magnetic interface. This device was probably the very last one available in my geographic area. The whole experience caused me to research the safety of software on medical devices generally.

And ever since then I've been grateful to have that device. As exploit after exploit were published I was sound in the knowledge that at the very least, my device would be safe from remote attack. This became less hypothetical as I (like many other women on the Internet as I have come to understand) have received actual threats to my safety and well being.

I was a little worried about getting a new device, but had relaxed after I spoke to a nurse practitioner a couple of years ago. He said that anyone could ask for their device's radio telemetry to be disabled after it was publicized that Dick Cheney had the wireless functionality disabled in his device. Apparently, if this was true at the time, it is no longer true, and with only a few months of power left on my current device, I was faced with the prospect of not only having a device to which I couldn't see the source code, but also one that would be wirelessly accessible with little or no security on it.

I went to the Heart Rhythm Center to begin the process of planning for the replacement and met with Abigail Silver, a nurse practitioner. She was kind enough to involve me in the process of contacting the manufacturers to ask them if they had any devices either without radio telemetry or with radio telemetry that could be disabled. On speaker phone, Abigail called the major manufacturers. One by one the representatives we spoke to all told me that my request was not possible. Some of the representatives were cagey. One manufacturer suspiciously asked Abigail to take the phone of speaker in order to tell her that the company did have a device without radio telemetry, though it turned out that the device was just a pacemaker and not a defibrillator. Some of the representatives were defensive. When I explained how vulnerable medical devices are, the Biotronik representative bragged "Our devices are hack proof." When I explained that this was probably not the case, he boasted that Biotronik's devices had never been shown to be vulnerable, and did not listen to my reasons why that would not necessarily indicate the devices to be truly secure from any attack.

At the end of these calls, I was in total despair. How is it possible that none of the major device manufacturers recognize the danger in having these devices enabled with wireless access? Some of the representatives we spoke to had no knowledge of the exploits that were widely publicized. I thought the biggest challenge I was going to face was once again seeking the source code to my body, but this was a direct and immediate threat to my safety and well being.

Fortunately, at the last minute of my time at the Center, my doctor remembered a small manufacturer making inroads in the United States. Abigail called them and happily, they do have a device I'll likely be able to use. It is with great relief that I'm writing this blog post. I continue to learn so much about the medical system and our fragile relationship with software, I hope I can make the time to explore each relevant part of this experience and research in future posts.

[1] My battery ran out a bit faster that it would ordinarily have because I got three unnecessary shocks. One shock was because the device was callibrated too sensitively (I was working out at the gym, and my device thought my heart was beating twice as fast as it was). Two shocks were while I was pregnant, and I was having some palpitations, as pregnant women often do.

[2] I also found a great HCM specialist, Dr. Harry Lever, who understands how important ethics are in technology and medicine (and how we need to safeguard against corporate interests), and more general cardiologist Dr. Olivier Frankenberger who have been great resources in my healthcare journey.

Getting Started with Linux Development and Compliance: An Interview with Christoph Hellwig

by on February 22, 2017

Christoph Hellwig is a Linux developer, responsible for the code for several filesystems and the NVM Express drive. He’s a member of Conservancy’s GPL Compliance Project for Linux Developers and the plaintiff in the case against VMWare, which still awaits appeal. We recently had a chance to catch up with him to hear how he got started working on Linux, what advice he would give newcomers, and why he supports Conservancy’s work.

Q: How did you become interested in Linux? Is there a contribution you are most proud of?

CH: When I was a kid in Germany I started using Usenet and got myself into programming more or less by accident. That lead to learning about Linux and installing it at home. Soon after I started hacking kernel to make the sound card in my computer work under Linux.

Q: Why did you join Conservancy’s GPL Compliance Project For Linux Developers?

CH: I decided that fighting copyright violations on my Linux code wasn’t a task I could take on alone. Based on that I decided to join the Conservancy’s GPL Compliance Project for Linux Developers, which is a very open project and also includes other kernel developers I respect a lot.

Q: What advice would you give to someone who is starting out in the Linux kernel today?

CH: Try to scratch an itch instead of just looking for an easy task that looks good on a resume. For example fix something that annoys you or a friend. Or try to upstream support for an embedded device you use. Don’t send cleanup patches for random code—that’s a good way to be seen as someone who is only interested in polishing his or her resume with kernel commits.

Q: Why do you choose to support Conservancy, in addition to volunteering your time to promote free software and compliance?

CH: I am very impressed with Conservancy’s work. Not only in the compliance program where I work closely with the Conservancy, but also how it helps a lot of free software projects to manage their affairs.

Join Christoph and support Conservancy today! Supporters sustain all of this work we do, from fiscal sponsorship for projects, to compliance work on their behalf.

Git Merge and FOSDEM 2017!

by on February 17, 2017

For me, FOSDEM this year started two days early with Git Merge, the annual Git conference. Git Merge is organized by GitHub, and so far in all three years of its organization the conference has donated the proceeds from ticket sales to Conservancy! I’d been hoping to get to Git Merge one of these years, so I was very excited with the organizing team asked me to do an talk introducing Conservancy.

I got to kick off the conference, and introduced myself by explaining how investigating my heart condition and defibrillator caused me to become passionate about software freedom. I then delved into what Conservancy does and in particular talked about some of the work we’ve done with Git. The talk had a good impact, and all day long I was able to speak with people who were excited about Conservancy and thinking about the ethics of all of our software. It’s always especially thrilling to speak at our member projects’ conferences. I love meeting up with leadership committee members and also putting faces to the names that we see go by while monitoring the activities of our projects.

Photo by Neil McGovern

FOSDEM is an extraordinary conference. A two-day whirlwind of activity, there are many more worthwhile things there than any one person can get to. The whole conference is completely community run and organized. Companies can buy neither stands nor talks in any of the devrooms, which keeps the quality really high. Thousands of people attend FOSDEM and there are great conversations happing everywhere. I find it incredibly difficult to balance seeing people, attending talks (even in my own devroom) and keeping the Conservancy stand running.

Fortunately for us, the FOSDEM organizers were very thoughtful and placed the Conservancy stand just across the hallway from the Legal & Policy devroom, which Bradley and I help organize. I spent most of the time running between the short distance between the two.

One of the major highlights for me was being at the stand with volunteers. Mike McQuaid (of Homebrew, another member project) and Spencer Krum both spent significant time at the booth loudly heckling people into becoming Conservancy Supporters. Stefan Hajnoczi (of QEMU, also a member project) took a quieter but no less dedicated approach. Michal Čihař spent a huge portion of his conference in our booth helping to promote phpMyAdmin and Conservancy. Having people who are giving of their time already so eloquently advocating for our organization was powerful, and helped me feel so energized about Conservancy. We’d launched our match donation that day, and I think it generated a lot of excitement at the booth. We also were lucky to be right next to the stand for one of Conservancy’s newer projects, the Godot Game Engine, which was very fun and convenient.

The Legal & Policy devroom is always fantastic, and while I wound up at the stand and in meetings for much of my time at FOSDEM, I still participated enough to really get a lot out of it. I spoke on a panel about permissive/dismissive licenses and another about fiscal sponsorship entities in Europe. FOSDEM video volunteers have been great, and video is already up for most of the sessions. A huge shout out to Tom Marble who does most of the heavy lifting in organizing the room. There are a lot of great places to discuss imporant legal issues but the FOSDEM devroom is one of my favorites. The talks this year were particularly interesting. I’m looking forward to catching up on the videos of the ones I missed.

I also really enjoyed Bradley’s keynote (we closed the stand down a little early so that we could all attend). Bradley is such an inspiring speaker, and I think he distilled a lot of the major issues facing copyleft and copyleft compliance.

I think part of the magic of FOSDEM is that it’s contained in a single weekend. While it’s inevitable to feel like you wished there were more time to catch up with all of the exceptional people who attend, and it’s exhausting to have no downtime over two days (I even missed the GNOME beers!) it’s just the right amount of time to fully immerse yourself in all things free software.

Software Freedom Can Avoid the Looming Dystopia

by on February 14, 2017

I encourage all of you to either listen to or read the transcript of Terry Gross' Fresh Air interview with Joseph Turow about his discussion of his book “The Aisles Have Eyes: How Retailers Track Your Shopping, Strip Your Privacy, And Define Your Power”.

Now, most of you who read my blog know the difference between proprietary and Free Software, and the difference between a network service and software that runs on your own device. I want all of you have a good understanding of that to do a simple thought experiment:

How many of the horrible things that Turow talks about can happen if there is no proprietary software on your IoT or mobile devices?

AFAICT, other than the facial recognition in the store itself that he talked about in Russia, everything he talks about would be mitigated or eliminated completely as a thread if users could modify the software on their devices.

Yes, universal software freedom will not solve all the worlds' problems. But it does solve a lot of them, at least with regard to the bad things the powerful want to do to us via technology.

Next page (older) » « Previous page (newer)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 [47] 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68