![[RSS]](/static/img/feed-icon-14x14.2168a573d0d4.png) Conservancy Blog

Conservancy Blog

Reflecting on FISL16

by on July 14, 2015

I'm back from Brazil where I attended FISL. I had the honor of presenting three talks! And they were three of my favorite topics: the importance of compliance and the suit against VMware, bringing more women to free and open source software and why I care so much about software freedom in the first place. It was a very fun conference. Besides doing the talks I was able to do a few press interviews too. And of course I loved meeting Brazilian hackers and software freedom activists.

Attendees seemed very interested in enforcement and the VMware suit. I was happy to see support for this work, and there was discussion about local copyright holders signing up to the coalition. It really seems that folks are starting to see the downsides of noncopylefted projects and are frustrated by the pervasiveness of GPL violations.

One of my favorite moments of the conference was the response to my talk about gender diversity. I admit that it's disappointing that this talk is always attended disporportionately by women. As I sometimes say in the talk itself, it doesn't make a lot of sense for the burden of this work to fall only on women. There are so few women right now in free software (1-11% at most) that it would be impossible for us to do it on any meaningful scale alone. Plus it's not fair to expect women to undertake this work on top of their other contributions to free software (many women understandably don't want to think about gender issues at all). Men can make a tremendous impact on this area. Most of our Outreachy mentors are men, and as the dominant group in free and open surce software, it's men who can fundamentally change the culture to be more welcoming to women and other underrepresented groups. Nonetheless, it was amazing that the "mob" after my talk was mostly women. It was great to meet so many women who are leaders in Latin America and to hear about their extraordinary work. I was interviewed after the talk and was askd to give some tips for women getting started in free software.

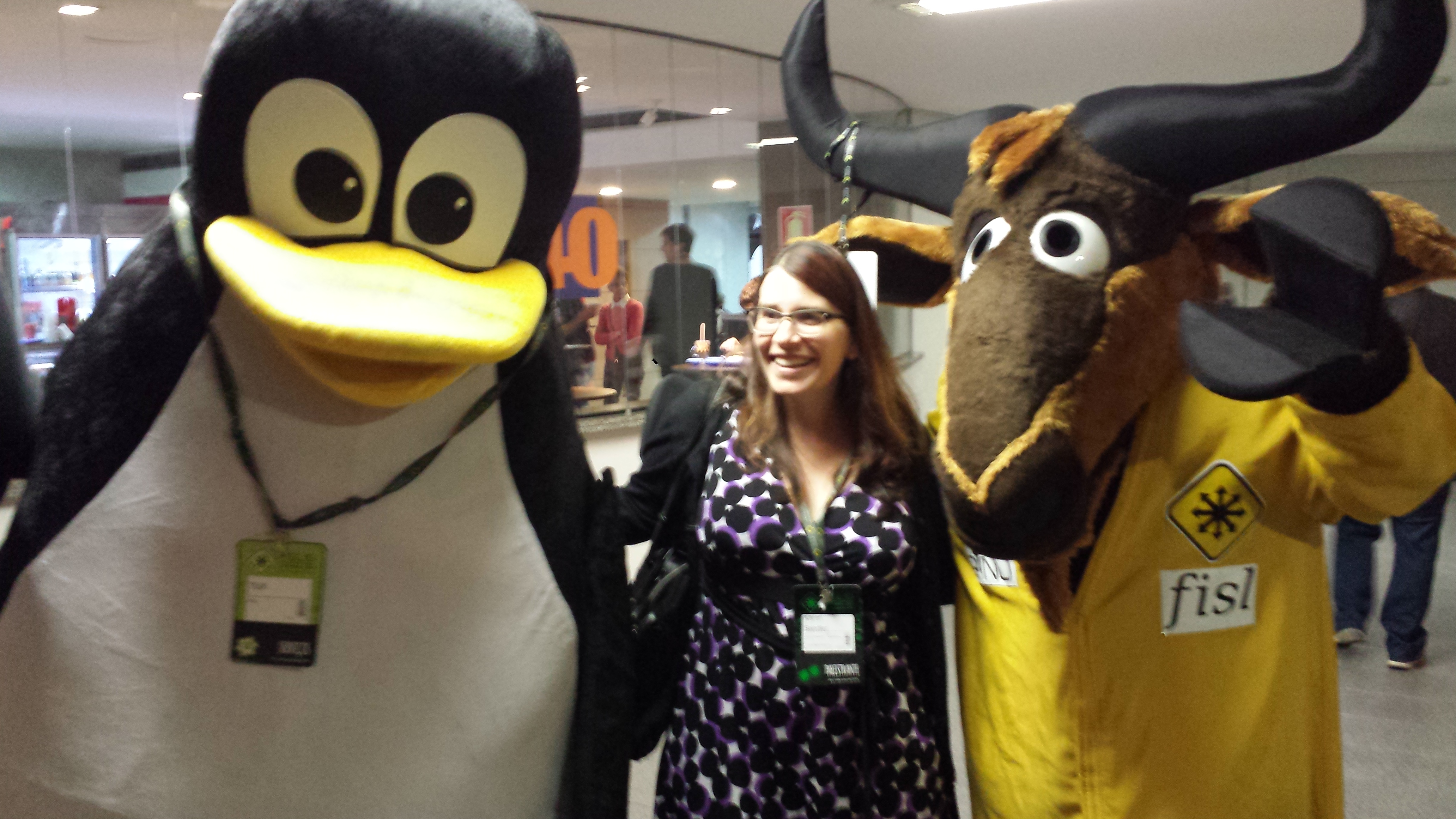

The conference had a very different feel to it than a lot of the other conferences I attend. It was a community run conference (along with that awesome community feeling, a lot of students, etc.) but it's such a big conference that it has some things that community conferences often don't have. Like GNU and Tux mascots (thanks to Deb Nicholson for the photo)!

I loved seeing schoolkids excited to be there and quite a number of really little kids with GNU and Freedo shirts and toys.

There was also a lot of love for GNOME, and it was great to meet up with people I don't get to see very often, especially since I'm missing GUADEC this year. Plus we got to settle some outstanding Linux kernel/systemd issues.

FISL is an excellect conference - a wonderful alternative to the corporate trade association conference ciruit. I hope to be able to return some time in the future. Now to get ready for OSCON next week...

Conservancy Supporters!

by on April 20, 2015

I just have to share this picture from last week in Barcelona. It was fantastic to see Conservancy Supporters showing off their shirts and by proxy their support of Conservancy's activities. I was so happy to hear so much positive feedback on the VMWare lawsuit, filed by Christoph Hellwig. Last month, Donald Robertson got a round of applause during my LibrePlanet keynote just for wearing a Conservancy t-shirt! When we first launched the Supporter program I wrote about how impressed I was by the caliber of the intitial wave of Supporters, and as you can see from the notable folks in this picture, the trend has continued as we more than double our numbers. You can get yours by becoming a Conservancy Supporter today!

Thanks Stefano, John, and Jim plus Carlo Piana for taking the photo!

My Favorite Time to Support Charitable Nonpofits

by on April 15, 2015

Most nonprofits push for donations in December to try to cash in on the giving spirit and the end of the calendar year deadline for tax deductions. Conservancy is no exception - we launched our Supporter program at the beginning of December and promoted that as much as we could until the end of the year. Because this is on everyone's minds, there are a lot of blogposts recommending which charities you should donate to and match challenges lined up to get people excited. While the end of the year is a fine time to contribute to nonprofits, to me the best time to make donations is today. Today is Tax Day in the United States. It's the deadline that everyone scrambles against to file their taxes and hopefully, if this is you, then by the end of today you've made it [1]!

If you got a refund, putting some of what feels like a windfall to a good cause is just the thing. It's nice not to have to worry about remembering to make donations at the end of the year. And if you wish you'd paid less in taxes, it may benefit you next year to make more charitable contributions./p>

Even if you're outside the U.S. or if you're not in a tax situation where charitable donations make a difference to you the donation will make a huge difference to your favorite nonprofits and their ability to budget, as many of them are in the first quarter of their fiscal year.

[1]As painful as it may have been. I'm glad I'm on the FSF's High Priorities Projects Committee to push for inclusion of tax software. It's really upsetting that there's no free alternative.

April 3rd last chance to donate towards Compliance Match

by on April 2, 2015

Tomorrow is the last day to contribute towards Conservancy's $50,000 anonymous match! We've made great progress and are tantalizingly close to making the full goal. We're now 97.8% of the way there. You can help us close the gap — just 11 Supporter sign ups will do it!

If you want more details about the suit that Christoph Hellwig is bringing against VMware in Germany, you can read our FAQ or watch the video below of my keynote at LibrePlanet on the topic.

Next page (older) » « Previous page (newer)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 [63] 64 65 66 67 68