![[RSS]](/static/img/feed-icon-14x14.2168a573d0d4.png) Conservancy Blog

Conservancy Blog

Managing Diabetes in Software Freedom

by on November 6, 2025

Our member project representatives and others who collaborate with SFC on projects know that I've been on part-time medical leave this year. As I recently announced publicly on the Fediverse, I was diagnosed in March 2025 with early-stage Type 2 Diabetes. I had no idea that that the diagnosis would become a software freedom and users' rights endeavor.

After the diagnosis, my doctor suggested immediately that I see the diabetes nurse-practitioner specialist in their practice. It took some time get an appointment with him, so I saw him first in mid-April 2025.

I walked into the office, sat down, and within minutes the specialist asked me to “take out your phone and install the Freestyle Libre app from Abbott”. This is the first (but, will probably not be the only) time a medical practitioner asked me to install proprietary software as the first step of treatment.

The specialist told me that in his experience, even early-stage diabetics like me should use a Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM). CGM's are an amazing (relatively) recent invention that allows diabetics to sample their blood sugar level constantly. As we software developers and engineers know: great things happen when your diagnostic readout is as low latency as possible. CGMs lower the latency of readouts from 3–4 times a day to every five minutes. For example, diabetics can see what foods are most likely to cause blood sugar spikes for them personally. CGMs put patients on a path to manage this chronic condition well.

But, the devices themselves, and the (default) apps that control them are hopelessly proprietary. Fortunately, this was (obviously) not my first time explaining FOSS from first principles. So, I read through the license and terms and conditions of the ironically named “Freestyle Libre” app, and pointed out to the specialist how patient-unfriendly the terms were. For example, Abbott (the manufacturer of my CGM) reserves the right to collect your data (anonymously of course, to “improve the product”). They also require patients to agree that if they take any action to reverse engineer, modify, or otherwise do the normal things our community does with software, the patient must agree that such actions “constitute immediate, irreparable harm to Abbott, its affiliates, and/or its licensors”. I briefly explained to the specialist that I could not possibly agree. I began in real-time (still sitting with the specialist) a search for a FOSS solution.

As I was searching, the specialist said: “Oh, I don't use any of it myself, but I think I've heard of this ‘open source’ thing — there is a program called xDrip+ that is for insulin-dependent diabetics that I've heard of and some patients report it is quite good”.

While I'm (luckily) very far from insulin-dependency, I eventually found the FOSS Android app called Juggluco (a portmanteau for “Juggle glucose”). I asked the specialist to give me the prescription and I'd try Juggluco to see if it would work.

CGM's are very small and their firmware is (by obvious necessity) quite simple. As such, their interfaces are standard. CGM's are activated with Near Field Communication (NFC) — available on even quite old Android devices. The Android device sends a simple integer identifier via NFC that activates the CGM. Once activated — and through the 15-day life of the device — the device responds via Bluetooth with the patient's current glucose reading to any device presenting that integer.

Fortunately, I quickly discovered that the FOSS community was already “on this”. The NFC activation worked just fine, even on the recently updated “Freestyle Libre 3+”. After the sixty minute calibration period, I had a continuous readout in Juggluco.

CGM's lower latency feedback enables diabetics to have more control of their illness management. one example among many: the patient can see (in real time) what foods most often cause blood sugar spikes for them personally. Diabetes hits everyone differently; data allows everyone to manage their own chronic condition better.

My personal story with Juggluco will continue — as I hope (although not until after FOSDEM 2026 😆) to become an upstream contributor to Juggluco. Most importantly, I hope to help the app appear in F-Droid. (I must currently side-load or use Aurora Store to make it work on LineageOS.)

Fitting with the history that many projects that interact with proprietary technology must so often live through, Juggluco has faced surreptitious removal from Google's Play Store. Abbott even accused Juggluco of using their proprietary libraries and encryption methods, but the so-called “encryption method” is literally sending an single integer as part of NFC activation.

While Abbott backed off, this is another example of why the movement of patients taking control of the technology remains essential. FOSS fits perfectly with this goal. Software freedom gives control of technology to those who actually rely on it — rather than for-profit medical equipment manufacturers.

When I returned to my specialist for a follow-up, we reviewed the data and graphs that I produced with Juggluco. I, of course, have never installed, used, or even agreed to Abbott's licenses and terms, so I have never seen what the Abbott app does. I was thus surprised when I showed my specialist Juggluco's summary graphs. He excitedly told me “this is much better reporting than the Abbott app gives you!”. We all know that sometimes proprietary software has better and more features than the FOSS equivalent, so it's a particularly great success when our community efforts outdoes a wealthy 200 billion-dollar megacorp on software features!

Please do watch SFC's site in 2026 for more posts about my ongoing work with Juggluco, and please give generously as an SFC Sustainer to help this and our other work continue in 2026!

Join SFC for a Q&A on how to keep your sideloading, and other phone freedom tips

by on September 3, 2025

You may have heard that Google will be limiting sideloading in the next few months, which is likely to be enforced through Google Play Services, something that runs on virtually all Android phones. Google plans include blocking sideloading of apps where the developer has not shown their ID to Google. Many people have been asking us how they can support app developers who will not or cannot be involved in a Google-run identity verification program.

In particular, we've been increasingly hearing that Android users want to remove their dependence on Google, for this and many other reasons, including the tracking and surveillance that come with using Google Play Services and other Google apps. As a result, we will be hosting a Q&A session this week, in conjunction with folks from F-Droid, to discuss how to best remove proprietary Google code from your phone, and ensure that you control how your phone operates, and which apps can run on it (and from whom).

"Phone freedom tips, and related Q&A" video chat details:

- Friday, Sep 5 (2025), at 15:00 UTC (08:00 US/Pacific, 11:00 US/Eastern, 17:00 CEST)

- https://bbb.sfconservancy.org/b/den-i3x-a5u-vkq

We will cover the basics of which Google apps and other code you might be using, which of that you can remove while maintaining the use cases you have for your phone, and how to adapt use cases to potentially further reduce reliance on other non-free tools that prevent you from using your phone as you wish.

Among other options, we'll talk about how to use LineageOS on your phone, or another phone you might have already, what you can expect from alternate OSes in general, and how you can keep doing what you need, while giving yourself more control over what you can do in the future. Alongside participants from F-Droid, we will also discuss the F-Droid project, which hosts free apps that provide alternatives for non-free apps from Google Play, as well as classifying apps by how your data is handled, so you can maintain as much say over your privacy and freedom as possible.

We're excited to chat about how to improve your phone experience through the tools and expertise that software right to repair enthusiasts have created to ensure your phone and what you do on it is truly in your own hands!

Everyone is asking the wrong questions about TikTok

by on January 18, 2025

As we write this, everyone is wondering what will happen with TikTok in the next 48 hours. Social media as a phenomenon was designed to manufacture drama to sell advertising, and in this moment, the meta-drama is bigger than the in-App drama.

The danger of pervasive software is clear: powerful entities — be they governments or for-profit corporations — should not control the online narrative and remain unregulated in their use of personal data generated by these systems. However, the approach taken by Congress and upheld by SCOTUS remains fundamentally flawed. When there is power imbalance between a software systems' users and its owners, the answer is never “pick a different owner”.

Whoever owns ByteDance, the fundamental problem remains the same: users never really know what data is collected about them, and they don't know how the software manipulates that data when deciding what they are shown next. The problem can only be solved if users can learn, verify, and understand how that software works.

TikTok is a software system — implemented in two parts: somewhere, there is a server (or, likely, a group of servers), running the software that gathers and aggregates posts, and then there is the client software — the App — installed on users' devices. In both cases, ByteDance likely owns and controls both pieces of technology and is the only entity with access to the “source code” — the human readable software that can be studied and understood by human beings. When users download the TikTok App, they don't get that source code for the App, and certainly get no information about the software running on the servers.

If the USA operations of TikTok are sold to another entity, quite likely the software itself will remain in control of ByteDance. While the wording in the Act is expansive about the required divestment, it's likely the new USA owners wouldn't themselves receive the right to review or modify the source code — they could just receive a binary (non-source form) of that software. In that case, no one in the USA will have permission to review and verify that software behaves in a way that is in the interest of its USA users. The Act is vague on these details. Will complete, corresponding source code ultimately be considered part of “a qualified divestiture”? The Act simply leaves "an interagency process", with no guidance (to our knowledge) on the issue of server or App source code. (We have seen similar failures where government agencies with a duty to examine software found in medical devices do not actually even have access to the source code.)

The root problem is that the act doesn't require an action that would truly resolve the biggest threat to TikTok users in the USA. Users (and our government) should instead insist that, to operate in the USA, that ByteDance respect the software rights and freedoms of their users by releasing both the server and App components of the software under a “free and open source” (FOSS) license. FOSS respects the software rights of all by allowing everyone to review, modify, improve, and reinstall their own versions of the software. By technical necessity, this means that everyone could understand the communication protocol between the App and the servers. Users (or third-party App makers) could, for example, modify the App to no longer send users down the rabbit hole of toxic recommended posts, or refuse to transmit user usage data back to the servers in China. FOSS is the best method we have to democratize technology and its algorithms.

Industry will, of course, ask how could a new company, build around a purely FOSS platform, ever generate the revenue necessary to run the network of servers and implement needed improvements to the App? The answer to that is, in fact, part of the beauty to this solution. The primary reasons that sites like TikTok are so toxic is inherent in their business model: privacy-unfriendly data gathering to sell targeted advertising. Indeed, these issues are raised as serious concerns by individuals from all over the political spectrum and they are the primary reason the initial bill passed the House so easily. If we demanded a FOSS and transparent business model, TikTok would have little choice but to move to subscription-based revenue instead of advertising.

As we continue on the dystopian path where most of our technological solutions are funded primarily by advertising and massive, privacy-invading data collection, we must decide if the price that we pay for this technology is just too high. From our perspective, $14.99/month (plus full transparency and software rights) looks a lot better than $0 (plus no privacy and a daily dose of advertisements and occasional CCP propaganda). As the saying goes, if you don't pay for the product, you are the product.

Furthermore, a mandated FOSS release more directly exposes the true problem that the mandated sale tried to solve. We are not politically naïve; we know ByteDance would resist releasing TikTok (server and App) as FOSS just as much as they resisted the mandated sale. But the real problem we have is that we simply don't know if the Chinese government has undue influence over TikTok or not. We have that problem primarily because we cannot examine their opaque technology. Transparent technology leads the only way to the truth in our software-controlled world.

2024 End-of-Year Fundraiser Succeeds: over $480k to support software freedom

by on January 16, 2025

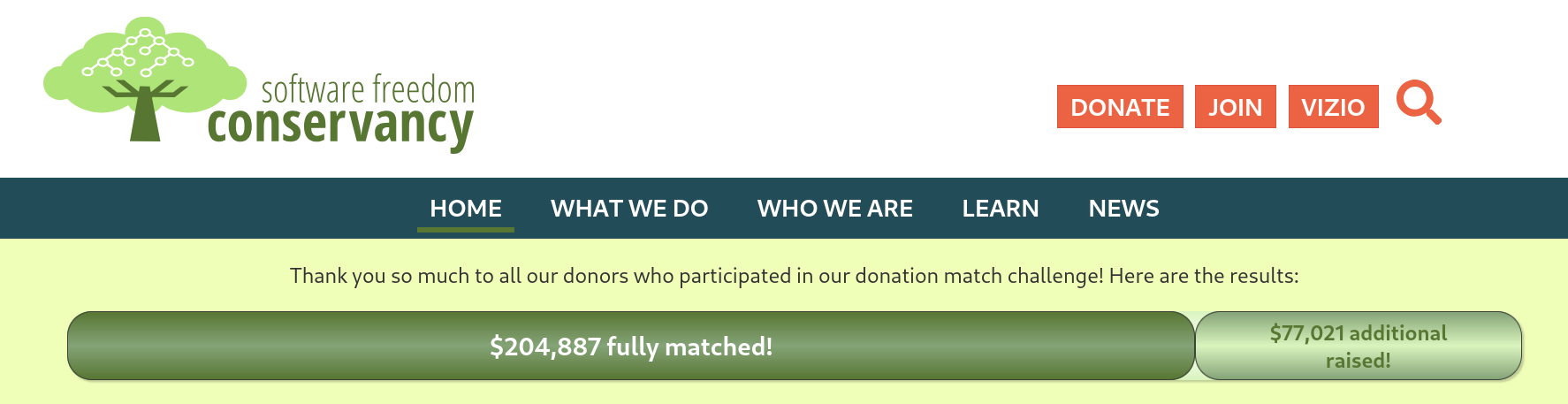

We thank both donors who offered this historic $204,877 match & those who gave to help to exceed the challenge

In late November, SFC, with the help of a group of generous individuals who pledged match gifts large and small, posted a huge challenge to our donors. We were so thankful for the donors who came together to offer others a match challenge of $204,877 — which was substantially larger than any of our match challenges in history.

Donors heard our ask, and we were even more thankful of all the donors who responded. Toward the end, we were so overwhelmed by last minute response that we were tabulating updates by hand. We saw so many donors who had already given coming in for another $10, $50 or $100 to get us there. We made the match primarily because of the hundreds of small donors who came in with Sustainer amounts, and we thank those small donors so much for often doing a bit extra: so many of you hit the $512 and even the $1024 button instead of the minimum of $128. It means so much to us when we see a donor who gave $128 in 2023 double their donation for 2024 — you all made this match challenge succeed. We also so appreciate the donors who, despite experiencing financial challenges, gave smaller amounts when it was a stretch for them to give at all.

Most surprising of all, an anonymous donor who in the past has made a very large donation around the time of FOSDEM came in early this year. That donation bursts us right through our status bar and puts us well over. We've raised over $475,000 this season, which is now reflected on our fundraiser status bar. (We're still tabulating and entering the paper checks and ACH/wire transactions that came during the final days of the fundraiser, so the number may soon increase even more!)

We are truly humbled. Every year, our staff is working tirelessly through the holiday season to make sure we balance our work and fundraising. Every dollar you all give us is noticed and appreciated, and gets us there, step by step.

SFC does receive some grants and corporate sponsorship for which we are also grateful, but the bulk of our funding comes from individual donors, like you. Fundraising is (sometimes annoyingly) mandatory work that as a small staff we must do in addition to our normal work. Nevertheless, it's a simple fact that the more you donate, the more program activity we can do. In essence, you make our important work for software freedom and rights.

Next page (older) » « Previous page (newer)

1 [2] 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68