![[RSS]](/static/img/feed-icon-14x14.2168a573d0d4.png) Conservancy Blog

Conservancy Blog

Displaying posts

tagged security

![]()

Prioritizing software right to repair: engaging corporate response teams

by on February 3, 2024

Across organizations who develop and deploy software, there are a wide range of time-sensitive concerns that arise. Perhaps the most diligent team that responds to such time-sensitive concerns is the cybersecurity team. It is crucial for them to quickly understand the security concern, patch it without introducing any regressions, and deploy it. In extreme cases this is all done within a few hours — a monumental task crammed into less time than a dinner party (and often replacing such a social event at the last minute; these teams are truly dedicated).

Many other teams exist across organizations for different levels of risk and concern. In our experience, on average among many companies, the team that receives among the lowest priorities is the team that responds to concerns about a company's copyleft compliance. Now we can think of some reasons for this: the team is often not connected to the team that collated the software containing copylefted code, or that latter team was not given proper instruction for how to comply with the licenses (and/or does not read the licenses themselves). So the team responding when someone notes a copyleft compliance deficiency is ill-equipped to handle it, and is often stonewalled by developer teams when they ask them for help, so the requests for correct source code under copyleft licenses usually languish.

With this in mind, we at SFC are helping prioritize the copyleft compliance concerns an organization may face due to some of the above. To reflect the importance of teams responding to copyleft compliance concerns, we recommend that companies create a team that we are calling a "Copyleft Compliance Incident Response Team" (CCIRT). This will help convey to management the importance of properly staffing the team, but also how it must be taken seriously by other teams that the CCIRT relies on to respond to incidents. Where companies employ Compliance Officers, they will likely be obvious leaders for this team.

Now some companies may not need a CCIRT. Unlike security vulnerabilities, failing to comply with copyleft licenses is entirely preventable. If you know your company already has policies and procedures that yield compliant results (of the same form as compliant source candidates that we praise in the comments on Use The Source), then there is no need for a CCIRT. However, our experience shows that most companies do not have such policies and procedures, in which case a CCIRT is necessary until such policies and procedures can reliably produce compliant source candidates from the start.

We recently launched Use The Source (alluded to above), which helps device owners and companies see whether source code candidates (the most important part of copyleft compliance) are giving users their software right to repair, i.e. whether they comply with the copyleft licenses they use. We realize companies may be concerned about SFC publishing their source candidates before they have had a chance to double-check them for compliance, due to some of the issues with policies and procedures mentioned above. As a result, we are giving companies the opportunity to be notified before we post a source candidate of theirs, so that they can take up to 7 days to update the candidate with any fixes they feel may be necessary before we post it. And the sooner a company contacts us, the better, as we are offering up to 37 days from the launch of Use The Source before we publish candidates we receive. See our CCIRT notification timeline for details. For historical purposes, the additional grace period that we provided at launch time is detailed here.

We hope that this new terminology will help organizations prioritize copyleft compliance appropriately, and that everyone can benefit from the shared discussions of source candidates and their compliance with copyleft licenses. We look forward to working with companies and device owners to promote exceptional examples of software right to repair (through our comments on Use The Source) as we find them.

Copyleft Won't Solve All Problems, Just Some of Them

by on March 17, 2022

Toward a Broad Ethical Software Licensing Coalition

We are passionate about and dedicated to the cause of software freedom and rights because proprietary software harmfully takes control of and agency in software away from users. In 2014, we started talking about FOSS as fundamental to “ethical software” (and, more broadly “ethical technology”) — which contrasts FOSS with the unethical behavior that Big Tech carries out with proprietary software. Some FOSS critics (circa 2018) coined the phrase “ethical source” — which outlined a new approach to these issues — based on the assumption that software freedom activists were inherently complicit in the bad behavior of Big Tech and other bad actors since the inception of FOSS. These folks argue that copyleft — the only form of software licensing that makes any effort to place ethical and moral requirements on FOSS redistributors/reusers — has fundamentally ignored the larger problems of society such as human rights abuses and unbridled capitalism. They propose new copyleft-like licenses, which, rather than focusing on the requirement of disclosure of source code, they instead use the mechanisms of copyleft to mandate behaviors in areas of ethics generally unrelated to software. For example, the Hippocratic License molds a copyleft clause into a generalized mechanism for imposing a more comprehensive moral code on software redistributors/re-users. In essence, they argue that copylefted software (such as software under the GPL) is unethical software. This criticism of copyleft reached crescendo in the last three weeks as pundits began to criticize FOSS licenses for failing to prohibit Putin from potentially using FOSS in his Ukrainian invasion or other bad acts.

We have in the past avoided a comprehensive written response to the so-called “ethical source” arguments — lest our response create acrimony with an adjacent community of activists who mean well and with whom we share some goals, but with whose strategies (and conclusions about our behavior and motivations) we disagree. Nevertheless, the recent events have shown that a single, comprehensive response would help clarify our position on a matter of active, heated public debate and fully answer these ongoing criticism of FOSS and our software freedom principles.

The primary criticism is that FOSS licensing over-prioritizes the rights of software freedom above substantially more important rights and causes — such as sanctions against war criminals. This rhetoric implies that software freedom activists have “tunnel vision” about the relatively minor issue of the rights to copy, modify, redistribute and reinstall software while we ignore bigger societal problems. This essay gives a comprehensive explanation of the specific reasons why copyleft avoids the “scope creep” of handling moral and ethical issues that relate only tangentially to software — even though those moral issues are indeed more urgent and dire than the moral issue of software freedom.

Software Freedom Isn't The Most Important Human Right

I personally, and many of my colleagues, have been admittedly imperfect advocates for software freedom. For the last thirty years, Big Tech and their allies have unfortunately successfully convinced the public that rights for users to control their own software are unimportant, and even trivial. (Apple has even successfully convinced their biggest fans that Apple's ironclad device lock-down is in your interest as a consumer.) In that climate, software freedom activists often overcompensated for the tech community's trivialization of software rights — specifically, overstating the relative importance of software freedom when compared to other human rights. Our error left a political vulnerability, allowing the opposition to successfully even further trivialize users' rights. Critics capitalized on this miscommunication, and often claim that FOSS activists believe that software freedom is the most important human right. Of course, none of us believe that.

I suspect most software freedom activists agree with me on the following: while I do believe software freedom should be a human right, I don't believe that our society should urgently pursue universal software freedom at the expense of upholding the many other essential rights (such as those listed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights). Clearly many other rights are more fundamental. In a society that fails to guarantee those fundamental human rights, software freedom (by itself) is virtually useless. Those who would violate the most basic human rights will simply ignore the issue of software freedom, too. Or, even worse, such bad actors will gladly use any software, flagrantly in violation of any license, to bolster their efforts to violate other human rights.

Software freedom as a general cause becomes essential and relevant when a society has already reached a minimal level of justice. Indeed, I've spent much of my career as a software rights activist considering whether I should instead work on a more urgent cause — such as ending human trafficking, animal rights, or remedying climate change. Personally, the only valid moral justification for my personal focus on software freedom instead of those other rights is four-fold: (a) there is an increasingly limited number of qualified people who are willing to work on software freedom as a charitable cause at all, (b) there is an increasing number of talented people who are actively working to create more proprietary software and seeking to thwart software freedom and copyleft, (c) my personal talents are in the area of software production and authorship, not in areas directly applicable to other causes, and (d) an increasingly digitized society mean software rights slowly increase in importance as an “enabler right” to defend and protect other rights (just as Free Speech enables activists to expose (and hopefully prevent) atrocities and their cover-ups). In other words, I am unlikely to make any useful impact on any other cause in my whole career, whereas due to the unique match of my skills to the cause of software freedom, I have made measurable positive impact on software rights. I generally encourage activists to focus on tasks that directly coincide with their existing talents, and have tried to do the same myself.

So my argument starts in fervent agreement with the first point made by proponents of adding non-software ethical issues into copyleft licensing: yes, I absolutely agree there are social justice causes that are more urgent than the right to copy, modify, redistribute and reinstall software. That begs their question: then, why not immediately begin using all the tools, mechanisms and strategies used for FOSS advocacy to advocate for these other causes? The TL;DR answer is simple: because these tools, mechanisms and strategies are highly unlikely to have any measurable impact on those other causes, while using them for these other causes would ultimately minimize software freedom and rights unjustly.

Indeed, we need to make progress on the issue of software freedom, precisely because even while others are working to address and redress these other social justice issues, proprietary software (such as through proprietary AI-based advertising software that manipulates public opinion) is currently used to undermine these other causes. Universal software freedom would thwart Big Tech's efforts to undermine other causes. Proprietarization of software isn't the most heinous human rights violation possible; nevertheless, proprietarization of software does assist companies to do harm regarding other social justice causes. I conclude from that realization that our society should seek to make progress on both upholding the existing human rights already listed in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, and also seek to make simultaneous progress on key rights not listed there, such as software freedom. We also err as activists if one group of activists seeks to thwart another by falsely claiming the other group is “complicit in human rights abuses” merely due to a strategic disagreement.

Ultimately, copyleft (and other FOSS licensing) is a strategy, not a moral principle unto itself. The moral principle is that proprietary software is harmful to people because it forbids their right to control their own software, learn how it works, and remove spyware from it (among many other ills). That moral principle remains valuable and deserves some of our collective attention, even if there are other more urgent moral principles that deserve even more attention.

Copyleft Is The Worst Strategy, Except for all the Others

So, if the production of proprietary software harms society, then why not focus all efforts on lobbying legislators to make proprietary software illegal? This should be the first question any new software freedom activist asks themselves. After all, for those of us who live in societies with relatively minimal corruption and that are governed by the rule of law, we should seek to make criminal those acts that harm others.

Criminalizing proprietary software has always been, and remains, politically unviable. We should constantly reevaluate that political viability (which software freedom activists have done throughout the last three decades). But as of the time of writing, this strategy remains unviable, primarily due to the worldwide domination of incumbent unbridled capitalism and a near universal poor understanding of the harm that proprietary software causes and enables.

Another possible approach to ending proprietary software is a universal boycott on authorship of proprietary software (perhaps through mass unionization of software developers). This is one of my favorite “thought experiments”, as it shows how much power individual software developers have regarding proprietary software. However, this universal boycott is also politically unviable, at least as long as proprietary software companies continue to pay such exorbitant salaries relative to other fields of endeavor.

So, if we can't make proprietary software illegal, and we can't dissuade developers from taking piles of money to write proprietary software, what's the next best strategy? The answer is to organize people to write alternative software that is not proprietary. This was the strategy that the software freedom movement pursued in earnest beginning in the early 1980s, and currently remains our best politically viable strategy. However, this approach always contained a fundamental problem: such software can easily be used as a basis for proprietary software. Thus non-copylefted FOSS competes against itself, rather hopelessly, since the proprietary version will likely always be a feature or two ahead, and the FOSS version a bug or two behind. Copyleft is the innovative strategy designed specifically to address that specific problem. Without copyleft, the only possible approach to answering the harm of proprietary software is the aforementioned general strike of all software development, since non-copyleft FOSS can be and is regularly used as a basis for advancing proprietary software and Big Tech's interests.

Copyleft generally works reasonably well as a strategy, but it admittedly requires constant vigilance. Copyleft needs someone to enforce it, and resources to do that. Copyleft must withstand the pressure of proprietary software companies who seek to erode and question its validity. The primary conceit of those who seek to use a copyleft-style strategy to address other software-tangential social injustices is their apparent belief that merely writing policy into a software license has any chance of changing behavior on its own. It simply doesn't.

Other Mechanisms Are More Effective If Politically Viable

The Hippocratic License and similar efforts have a laudable goal: they seek to assure that companies who deal in software always respect human rights. However, advocacy for universally recognized human rights, as a social justice cause, does have access to better advocacy mechanisms that software freedom activism does not.

Most notably, almost everything listed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is illegal in the USA and in most other industrialized nations where the bulk of software development occurs. Also, it is certainly politically viable to improve those laws — for those rare cases where a violation of a particular universally recognized human right is legal. In short, because these other rights are much more widely accepted as fundamental by the public, we can employ other, better means (including those listed above that don't work for FOSS) to compel compliance by companies with these other principles.

Furthermore, copyleft is ill-suited as a mechanism to enforce any rights in places where human rights violations are common. For example, no one has ever bothered to enforce copyleft licenses in jurisdictions where corruption is rampant and the judiciary is easily bribed. Over the last twenty years, we've received many reports of GPL violations in the Russian Federation, but we don't pursue them — not because they shouldn't be addressed, but because, under Putin's regime, it's highly unlikely we can get a fair hearing to uphold software freedom and rights for Russian citizens. Copyleft relies on a well-formed rule-of-law for contracts and copyright to protect people's rights (of any kind). In jurisdictions that already hold human life and the rights of its people in low regard (or simply have an exceedingly corrupt government), it's a pointless symbolic act to also take away the permissions of software redistribution and modification for bad behavior (of any kind). Companies and oligarchs operating in a corrupt, unjust society will successfully ignore those injunctions, too.

Meanwhile, in jurisdictions with relatively less corruption, other systems besides distribution licenses function well to curtail bad behavior. For example, I've owned exactly two cars in my life here in the USA. While I concede there are many problems with corruption here, we have a relatively just society that usually respects the rule of law for contracts and copyrights. The cars that I purchased here did not have a license that said: if you drive dangerously with the vehicle, you cannot purchase and utilize cars in the future from that manufacturer. We don't look to the car manufacturers to enforce the ethical use of vehicles; we instead make traffic laws, with various escalating penalties, including a driver licensing structure that can be revoked temporarily or permanently for egregious acts. We don't require manufacturers to contract with drivers to pollute less; we instead create and enforce environmental regulation and incentives both before and after the time of purchase. Because such systems exist and because there is widespread societal consensus about what is or is not ethical driving behavior, there is no point in enforcing these rules using copyright and contracts that bind the vehicle's purchaser. A more resilient system (of traffic and environmental laws, and their enforcement) works to deal with the problem, and improving those laws is politically viable. Additional licensing terms from the car manufacturers (imposed at the point of sale of vehicles) would create a useless redundancy, since the penalties and remedies available under that license are substantially less severe than those available under the laws that regulate drivers.

There are strategies other than licensing changes that would likely work well to both build a stronger coalition for software freedom and rights and curtail the atrocities committed by Big Tech and their customers. These strategies might become political viable, and are worth pursuing in parallel and in coalition. For example, widespread unionization of tech workers (not over wages, which are generally high, but over other issues, such as bad behavior and policy by their employers) could both improve companies' respect of software freedom and handle many problems raised by those who seek tangential expansion of copyleft into non-software issues. For our part, Software Freedom Conservancy has done some work in this area by encouraging developers to begin insisting on better terms in their employment contracts. I do worry that a functioning coalition on these matters is exceedingly difficult to build (and the very fact this essay ultimately became necessary hints at the difficulty in building that coalition). We'd be glad to work in coalition with such activists to further those causes if they include software freedom as an issue that belongs on the coalition's agenda.

But that's a long-term, speculative action. Meanwhile, for software freedom, copyleft is the best-available compromise strategy — since software rights are not and cannot be defended in a more robust way (such as through direct legislation, as opposed to indirectly relying on the copyright and contract legal systems to assure the rights). Copyleft is a round-about strategy. Using copyleft as a strategy to impact broader ills that have more effective mechanisms to address those ills is (at the very least) wasted time and (possibly) downright counter-productive.

Copyleft Focuses On Coalition

In our increasingly politically divided society, omnibus social justice reform has always been exceedingly difficult. Copyleft works precisely because it holds together a very thin coalition — by confining the issues to only those that happen with software.

Consider this example: I became a vegetarian in 1992. It does bother me that software that I've written could potentially assist a slaughterhouse to run more efficiently. I obviously have considered licensing my software under terms that would forbid use in a slaughterhouse (and a dozen other activities that I personal morally oppose, including for the waging of war). However, hand-picking my most important social justice causes and stringing a copyleft clause on them would dissolve a rather thinly-held coalition of copyleft proponents. Successful advocacy for a given cause relies on building broad coalitions among people with widely disparate views on other topics. Imagine how difficult activism on climate change would be if activists working to end human trafficking claimed that activists working to address climate change were complicit in human trafficking because The Paris Climate Agreement does not include penalties if participating nation-states fail to meet benchmarks on reducing human trafficking. Coalition building is complex. Context matters.

In a diverse political ecosystem, elegant solutions that work “ok” often fare better than comprehensive-but-complex solutions. Copyleft's innovation is that the only action you can take that revokes your right to copy, modify, redistribute and reinstall the software is failure to give that same right to someone else. This elegance makes the copyleft strategy powerful and effective. “Porting” the copyleft strategy to other causes may seem that it would yield “more of a good thing”. But, in practice, that approach turns copyleft licenses into complex omnibus legislation around which coalitions will evaporate.

Relatedly, the most difficult hurdle of copyleft has always been the creation of software that was so enticingly useful that political opponents (i.e., proprietary software companies) would gladly give users the rights to copy, modify, and reinstall the software — in direct exchange for having the benefit of building their new software on top of the existing copylefted components (rather than rewriting it themselves). I do not see a viable path to create the necessary coalition that would, after agreeing on an omnibus list of social justice issues, also find the funding and volunteer labor necessary to build software (under that license) that would entice those who currently work against that list of social justice causes to stop working against those causes merely because they'd gain so much more from the software than they gain from violating the principles. Copylefted software in a vacuum, adopted only by other copyleft activists does not change behavior of bad actors. For example, imagine if we wrote into our licenses that all who copy, modify and distribute the software must cease use of fossil fuels. That's an important cause, but it's hard to imagine our software would be so useful that companies would accelerate their reduction of fossil fuel use merely to gain immediate the permission to copy, modify and redistribute that software.

Copyleft Requires Constant Vigilance

Copyleft isn't magic pixie dust that liberates software. In fact, likely one of the biggest flaws in copyleft design has been a gross underestimation of resources required for enforcement in the scenario we now have. Broad adoption of key copylefted components remains an important step to curtail proprietary software developers' mistreatment of users. The situation slowly improves as such developers incorporate copylefted software like Linux into their essential computing systems — provided that is done so in compliance with the license. However, violations on essential GPL'd components such as Linux and GCC are rampant and limited funding is available to resolve these violations and restore users' rights in the software. Big Tech has also been relentless and highly creative in thwarting our enforcement efforts.

Thus, even if not for my earlier strategic reasons that I oppose adding ethical-but-software-unrelated restrictions to FOSS licenses, I'd still oppose it on tactical grounds. Namely, there is no clear funding path whereby additional terms seeking to protect and advance software-tangential social justice causes could be adequately enforced to make a measurable difference in advancement of those causes.

FOSS Must Still Have a Conscience on Non-Software Issues

This essay merely argues that FOSS licenses are not an effective tool to advance social justice causes other than software freedom. It does not argue that FOSS communities have no duties to other causes and issues; in fact, they do have such a moral obligation. For example, FOSS developers should refuse to work specifically on bug reports from companies who don't pay their workers a living wage. I also recommend that FOSS communities create (alongside their Codes of Conduct for behavior inside the project), written rules of the types of entities that the projects will officially assist with volunteer labor, or (in the case of a commercial FOSS community or organization), what types of entities the community will engage in business deals.

At Software Freedom Conservancy, we regularly discuss at both the staff and Board of Directors level what other social justice issues that we have a moral obligation to incorporate. Most notably, we've been the home for Outreachy, a program our own Executive Director, Karen Sandler, helped create, and for which we are glad to have Sage Sharp on staff to work on full-time. We know that FOSS lags behind proprietary software development in welcoming and providing opportunities for underrepresented groups. We dedicate significant organizational resources on these issues through Outreachy and other newer programs (such as the Institute for Computing Research). We made a public statement that Trump's travel ban directly thwarted FOSS. We go beyond the mere legal requirements to create ethical and equitable hiring practices that are without bias. In defending the rights of users under copyleft, we do not leave other issues behind. I believe that the critics have simply not paid attention to, or are willfully ignoring, the holistic and intersectional approach that we have brought to FOSS.

Regarding Putin's FOSS Permissions Upon Invasion of Ukraine

Initially, only a few FOSS critics insisted on this radical change to copyleft licensing structure. The issue had fallen into the far background of our community — until the last few weeks. Specifically, many recently began asking whether we should redraft FOSS licenses to impose sanctions on Putin in retaliation for his violent and unprovoked invasion of Ukraine. Admittedly, FOSS licenses do not prevent Putin from incorporating existing FOSS already in his possession into his war machine. I personally have been a conscientious objector to all military action since 1990, so I am sympathetic. I have always felt the OSI's framing the discussion of military use of FOSS as a “field of use restriction” misses the point; it inappropriately analogizes software to physical materiel, and analogizes those who write FOSS to de-facto military contractors. Software, fundamentally, is the written word; while it “feels” like more than that to us, factually speaking, software is merely a written record of knowledge, methods, and instructions for how to solve digital problems. It is disturbing that the plans for heinous acts can sometimes be modeled as digital problems, and that some of those problems may be solvable with existing FOSS. But we must curtail and punish actual actions, not knowledge nor writing, nor the unfettered sharing of generally useful technical information. Particularly in cyber-warfare circles, some folks tend to talk about software as we did during the days when sharing encryption software was banned: as if certain software is more like bombs than books. I don't think we should concede that rhetoric; all software remains much more like books than it is like bombs.

Even if we choose to not take away the right to read from the Russian people, that does not mean that FOSS activists concede that nothing can be done. Our nations can, should, and many currently do, forbid commerce with Russia during this period. This can and should include embargoes of selling new books, new copies of software, providing services for improvements to software, and any other commercial activities that could inadvertently aid Putin's war effort. Every FOSS license in existence permits capricious distribution; software freedom guarantees the right to refuse to distribute new versions of the software. (i.e., Copyleft does not require that you publish all your software on the Internet for everyone, or that you give equal access to everyone — rather, it merely requires that those whom you chose to give legitimate access to the software also receive CCS). FOSS projects should thus avoid providing Putin easy access to updates to their FOSS. Indeed, FOSS licenses planned well for how to manage bad actors who want your software: all FOSS licensing authorities have upheld the right to capricious distribution — precisely so that the license would not compel any developer to provide software to a bad actor.

I suspect activists will continue to disagree about whether we have a moral imperative to change FOSS licenses themselves to contractually forbid Putin to copy, modify, redistribute and reinstall the FOSS he already has (or surreptitiously downloaded by circumventing sanctions). However, these horrendous events in Ukraine offer real world examples to consider the viability of expanding copyleft term expansion beyond software, and consider how it might work. My analysis is that such changes would only give us the false sense of having “done something”. Ultimately enforcement of such licensing changes would either be impossible or pointless. The very entities (such as the varied international courts and treaty organizations) that could enforce such terms will also have plenty of other war crimes and sanctions violations to bring against Putin and his cronies anyway. The penalties for the actions of war that Putin took will be much stronger than Putin's contractual breach or copyright infringement claim that could be brought under a modified copyleft license and/or the Hippocratic License.

Conclusion

Copyleft licensing is a powerful strategy. As a strategy, copyleft has both its upsides and downsides in its ability to advance the software freedom and rights of users. However, the proverbial hammer of copyleft will not help you when your problem is more like a screw than a nail. Having already dedicated my entire career to advance the copyleft strategy, I do feel honored that folks who care deeply (as I do) about other important social justice causes are seeking to apply that strategy to new types of problems. However, despite my lifelong love and excitement for copyleft, and perhaps because of it, it's my duty to point out that copyleft is not a panacea for all that ills our troubled world.

Copyleft works because it's the best strategy we have for software freedom, and because copyleft elegantly confines itself to the software rights of users. Attempts to apply the copyleft strategy to software-unrelated causes will (at the very least) fail to achieve the intended results, and at their worst, will primarily serve to trivialize the important issue of software freedom that copyleft was invented to accentuate.

Cyborg Lawyer 2.0, "Hack Proof"

by on April 6, 2017

It's been quite a number of years since I got my first defibrillator/pacemaker and, a little bit earlier than expected[1], the battery is now starting to run out. While the alarm hasn't started going off yet (it's set to go off every day a little after noon once the power gets below the 30 day replacement threshold), it's down to the point that this can happen at any moment. There's no way to recharge the battery, though device manufacturers are working on that for future models, so it's surgery to take out the old one and implant a new one. Of course, I've known this was coming for a while, but for various reasons I wasn't that worried about it. I mean, after all, I still don't have access to the source code in my current defibrillator. I was expecting status quo, with the inconvenience of surgery and recovery but instead was faced with the possibility of something much worse.

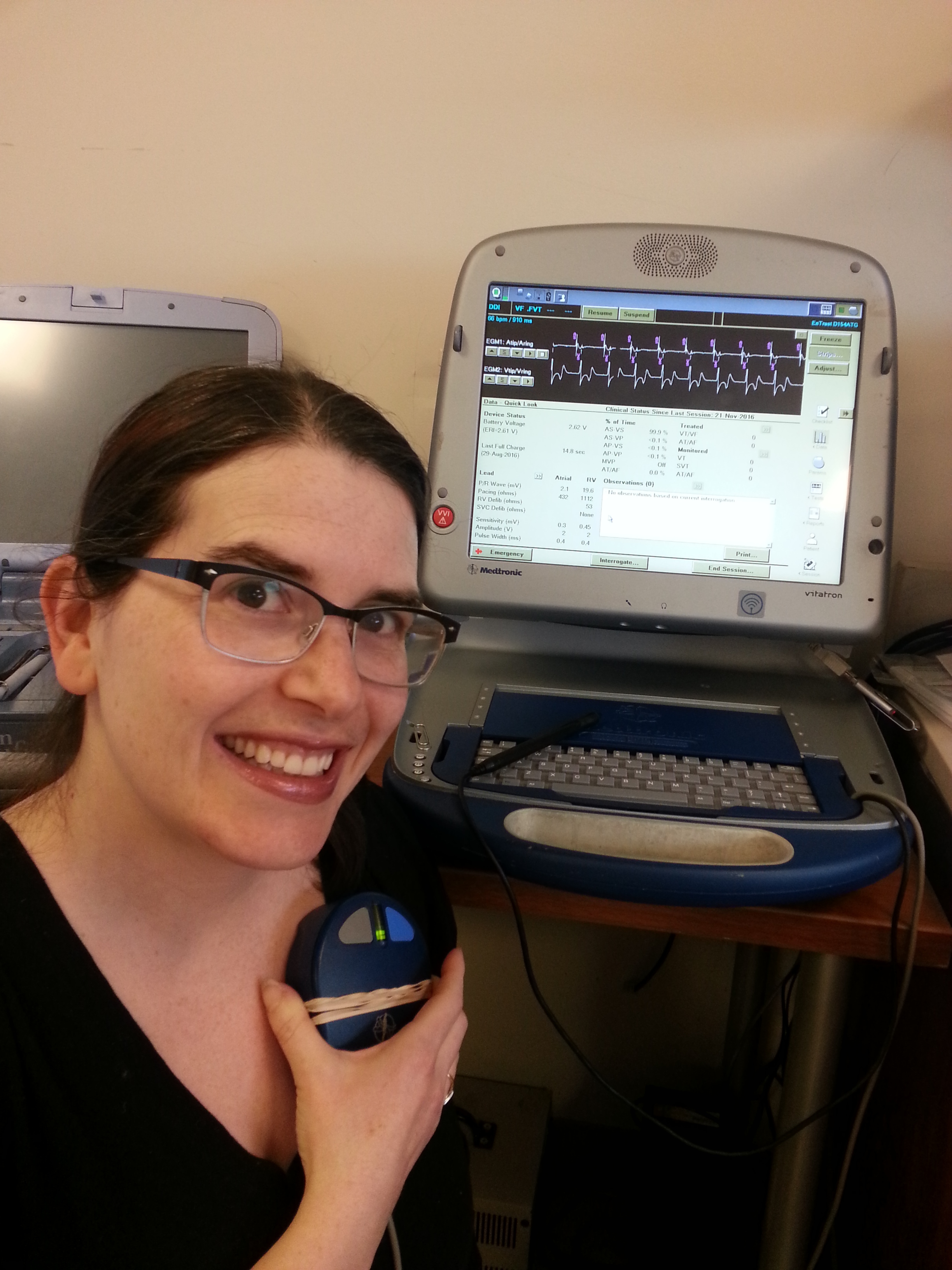

Karen getting her device interrogated via magnet

Back in 2007 when I first looked into getting my device, it was just before major research was published showing these devices to be vulnerable. I tried to convince my cardiologists and electrophysiologists that the issues around device security were critical, and that these device manufacturers got it backwards: no actual security but with proprietary software that cannot be reviewed or tested for safety. I explained that security through obscurity simply doesn't work. Initially, this did not go well at all but I finally found an electrophysiologist who got what I was saying [2]. He convinced me that I couldn't wait any longer to get the device and called around all of the local hospitals until he found one that had an old device that was still sterile. The older device had no wireless component, and could only be communicated with via a magnetic interface. This device was probably the very last one available in my geographic area. The whole experience caused me to research the safety of software on medical devices generally.

And ever since then I've been grateful to have that device. As exploit after exploit were published I was sound in the knowledge that at the very least, my device would be safe from remote attack. This became less hypothetical as I (like many other women on the Internet as I have come to understand) have received actual threats to my safety and well being.

I was a little worried about getting a new device, but had relaxed after I spoke to a nurse practitioner a couple of years ago. He said that anyone could ask for their device's radio telemetry to be disabled after it was publicized that Dick Cheney had the wireless functionality disabled in his device. Apparently, if this was true at the time, it is no longer true, and with only a few months of power left on my current device, I was faced with the prospect of not only having a device to which I couldn't see the source code, but also one that would be wirelessly accessible with little or no security on it.

I went to the Heart Rhythm Center to begin the process of planning for the replacement and met with Abigail Silver, a nurse practitioner. She was kind enough to involve me in the process of contacting the manufacturers to ask them if they had any devices either without radio telemetry or with radio telemetry that could be disabled. On speaker phone, Abigail called the major manufacturers. One by one the representatives we spoke to all told me that my request was not possible. Some of the representatives were cagey. One manufacturer suspiciously asked Abigail to take the phone of speaker in order to tell her that the company did have a device without radio telemetry, though it turned out that the device was just a pacemaker and not a defibrillator. Some of the representatives were defensive. When I explained how vulnerable medical devices are, the Biotronik representative bragged "Our devices are hack proof." When I explained that this was probably not the case, he boasted that Biotronik's devices had never been shown to be vulnerable, and did not listen to my reasons why that would not necessarily indicate the devices to be truly secure from any attack.

At the end of these calls, I was in total despair. How is it possible that none of the major device manufacturers recognize the danger in having these devices enabled with wireless access? Some of the representatives we spoke to had no knowledge of the exploits that were widely publicized. I thought the biggest challenge I was going to face was once again seeking the source code to my body, but this was a direct and immediate threat to my safety and well being.

Fortunately, at the last minute of my time at the Center, my doctor remembered a small manufacturer making inroads in the United States. Abigail called them and happily, they do have a device I'll likely be able to use. It is with great relief that I'm writing this blog post. I continue to learn so much about the medical system and our fragile relationship with software, I hope I can make the time to explore each relevant part of this experience and research in future posts.

[1] My battery ran out a bit faster that it would ordinarily have because I got three unnecessary shocks. One shock was because the device was callibrated too sensitively (I was working out at the gym, and my device thought my heart was beating twice as fast as it was). Two shocks were while I was pregnant, and I was having some palpitations, as pregnant women often do.

[2] I also found a great HCM specialist, Dr. Harry Lever, who understands how important ethics are in technology and medicine (and how we need to safeguard against corporate interests), and more general cardiologist Dr. Olivier Frankenberger who have been great resources in my healthcare journey.