Cyborg Lawyer 2.0, "Hack Proof"

by on April 6, 2017

It's been quite a number of years since I got my first defibrillator/pacemaker and, a little bit earlier than expected[1], the battery is now starting to run out. While the alarm hasn't started going off yet (it's set to go off every day a little after noon once the power gets below the 30 day replacement threshold), it's down to the point that this can happen at any moment. There's no way to recharge the battery, though device manufacturers are working on that for future models, so it's surgery to take out the old one and implant a new one. Of course, I've known this was coming for a while, but for various reasons I wasn't that worried about it. I mean, after all, I still don't have access to the source code in my current defibrillator. I was expecting status quo, with the inconvenience of surgery and recovery but instead was faced with the possibility of something much worse.

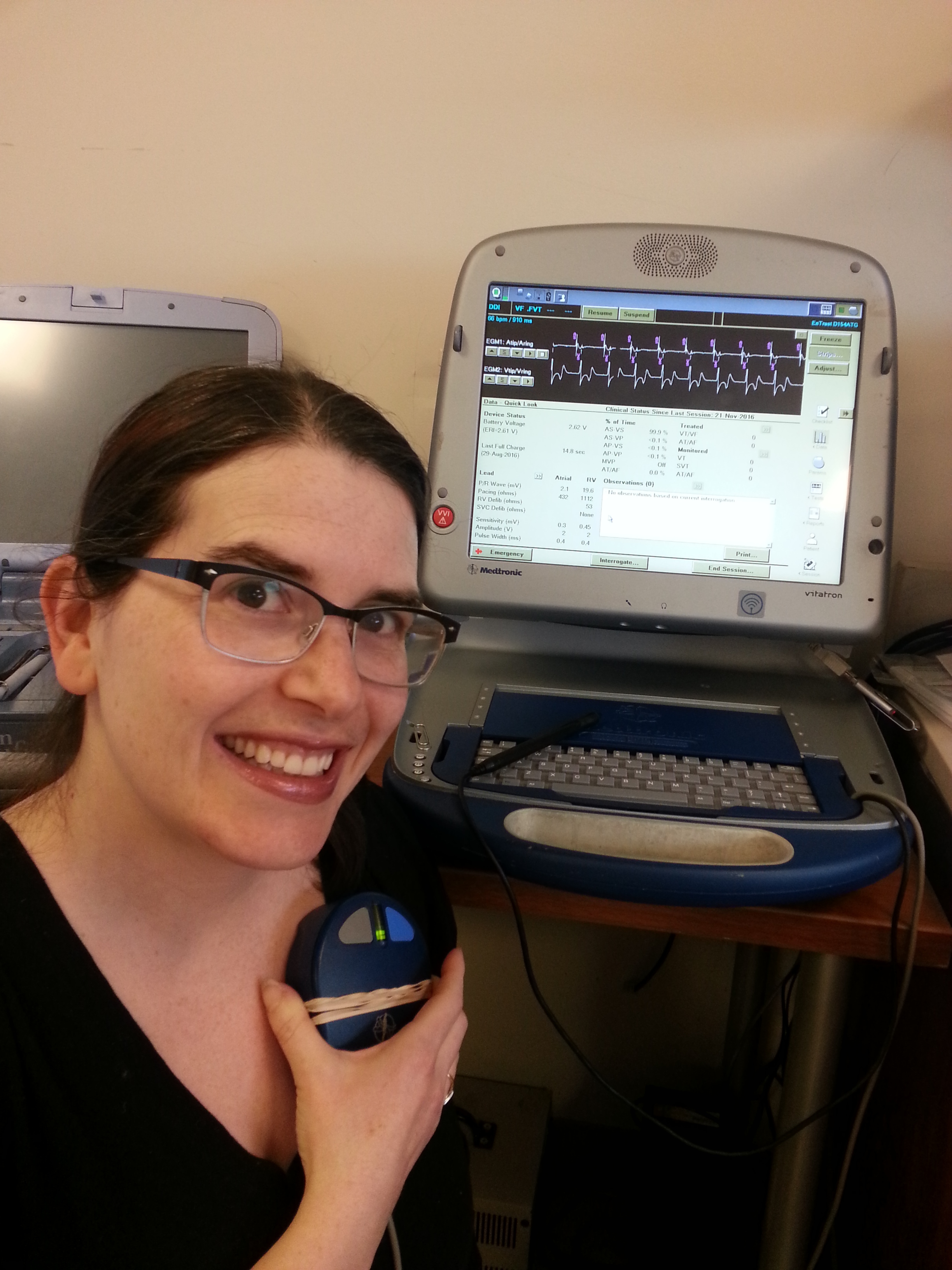

Karen getting her device interrogated via magnet

Back in 2007 when I first looked into getting my device, it was just before major research was published showing these devices to be vulnerable. I tried to convince my cardiologists and electrophysiologists that the issues around device security were critical, and that these device manufacturers got it backwards: no actual security but with proprietary software that cannot be reviewed or tested for safety. I explained that security through obscurity simply doesn't work. Initially, this did not go well at all but I finally found an electrophysiologist who got what I was saying [2]. He convinced me that I couldn't wait any longer to get the device and called around all of the local hospitals until he found one that had an old device that was still sterile. The older device had no wireless component, and could only be communicated with via a magnetic interface. This device was probably the very last one available in my geographic area. The whole experience caused me to research the safety of software on medical devices generally.

And ever since then I've been grateful to have that device. As exploit after exploit were published I was sound in the knowledge that at the very least, my device would be safe from remote attack. This became less hypothetical as I (like many other women on the Internet as I have come to understand) have received actual threats to my safety and well being.

I was a little worried about getting a new device, but had relaxed after I spoke to a nurse practitioner a couple of years ago. He said that anyone could ask for their device's radio telemetry to be disabled after it was publicized that Dick Cheney had the wireless functionality disabled in his device. Apparently, if this was true at the time, it is no longer true, and with only a few months of power left on my current device, I was faced with the prospect of not only having a device to which I couldn't see the source code, but also one that would be wirelessly accessible with little or no security on it.

I went to the Heart Rhythm Center to begin the process of planning for the replacement and met with Abigail Silver, a nurse practitioner. She was kind enough to involve me in the process of contacting the manufacturers to ask them if they had any devices either without radio telemetry or with radio telemetry that could be disabled. On speaker phone, Abigail called the major manufacturers. One by one the representatives we spoke to all told me that my request was not possible. Some of the representatives were cagey. One manufacturer suspiciously asked Abigail to take the phone of speaker in order to tell her that the company did have a device without radio telemetry, though it turned out that the device was just a pacemaker and not a defibrillator. Some of the representatives were defensive. When I explained how vulnerable medical devices are, the Biotronik representative bragged "Our devices are hack proof." When I explained that this was probably not the case, he boasted that Biotronik's devices had never been shown to be vulnerable, and did not listen to my reasons why that would not necessarily indicate the devices to be truly secure from any attack.

At the end of these calls, I was in total despair. How is it possible that none of the major device manufacturers recognize the danger in having these devices enabled with wireless access? Some of the representatives we spoke to had no knowledge of the exploits that were widely publicized. I thought the biggest challenge I was going to face was once again seeking the source code to my body, but this was a direct and immediate threat to my safety and well being.

Fortunately, at the last minute of my time at the Center, my doctor remembered a small manufacturer making inroads in the United States. Abigail called them and happily, they do have a device I'll likely be able to use. It is with great relief that I'm writing this blog post. I continue to learn so much about the medical system and our fragile relationship with software, I hope I can make the time to explore each relevant part of this experience and research in future posts.

[1] My battery ran out a bit faster that it would ordinarily have because I got three unnecessary shocks. One shock was because the device was callibrated too sensitively (I was working out at the gym, and my device thought my heart was beating twice as fast as it was). Two shocks were while I was pregnant, and I was having some palpitations, as pregnant women often do.

[2] I also found a great HCM specialist, Dr. Harry Lever, who understands how important ethics are in technology and medicine (and how we need to safeguard against corporate interests), and more general cardiologist Dr. Olivier Frankenberger who have been great resources in my healthcare journey.

Please email any comments on this entry to info@sfconservancy.org.