![[RSS]](/static/img/feed-icon-14x14.2168a573d0d4.png) Conservancy Blog

Conservancy Blog

Displaying posts by Vladimir Bejdo

An in-depth look at the social good of accessible free software: an interview with the MicroBlocks team

by on January 7, 2021

MicroBlocks is a free/libre visual programming language that can be used to make programs that can run autonomously on many popular microcontrollers, allowing users of all technical abilities to program microcontrollers for a vast variety of purposes and 'real world' applications. The MicroBlocks team also works to bring the language to youth underrepresented in computer science education as an introduction to computing in hopes of diversifying the field and getting more people engaged in using and producing free software, and works to increase awareness of the inequalities and problems of agency both in education and in embedded software that software freedom can help combat. MicroBlocks has been a Conservancy project since 2018.

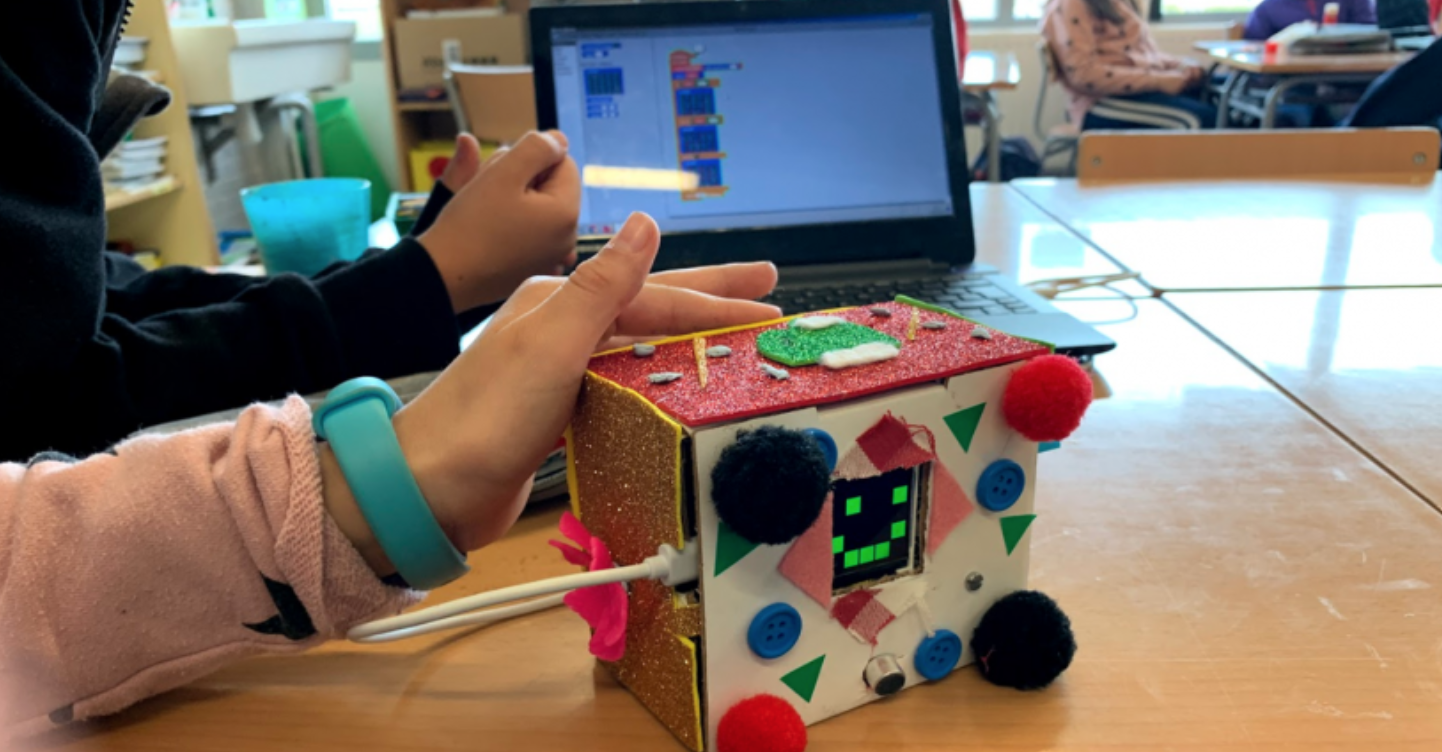

Creations by student using Microblocks. Photo © Citilab Cornellà Edulab, licensed CC BY-SA 4.0

John Maloney, Bernat Romagosa, and Kathy Giori, members of the project's Leadership Committee, took part in a remote interview with Vladimir Bejdo, a Conservancy intern, to discuss the project's origins, its future, and their views on the impact that MicroBlocks and free software as a whole can have in creating a more just, equitable future for all of us.

JM: John Maloney; KG: Kathy Giori; BR: Bernat Romagosa; VB: Vladimir Bejdo

VB: Tell me a bit about how you all got into free software to begin with – was there a particular moment or experience you could share that made you decide that free software was somehow important to get involved with?

KG: Early on in the days of web development via straight HTML, the ability to “view source” to learn and innovate upon others’ work was very powerful to me. I used Linux in the 1990s to support development of prototype military command and control technology using GPS, packet radio, and digitized maps (running on “luggable” laptops). But it wasn’t until I led a startup (starting in 1999) that I began to fully appreciate the importance of leveraging free and open source software, and the advantage of integrating business solutions built upon popular and stable packages and tools developed by others. Three “products” we implemented were: 1) writing “screen scraping” software to pull HTML from web sites and generate apps for the then-new wireless Palm VII devices, 2) an open source alternative to Microsoft’s Exchange server for businesses to manage email, calendars, etc., and 3) a “desktop on the net” service that offered personal cloud storage of email and files, with remote “anywhere” access in three ways: HTML (browser), VNC client to serve up your content in a full Linux desktop (with useful pre-installed apps), and a Palm VII app (very early “mobile” experience). I learned the importance between permissive and non-permissive software licenses (e.g., GPL) while at Qualcomm Atheros. I had to push very hard for permission to lead product development for upstream Linux wireless drivers, and to lead the conversion of a barebones internal Linux SDK to a full router stack called “QSDK” based on the OpenWrt wireless router distribution.

JM: My twin passions are programming language research and end-user programming. My first job after graduate school was working on the Self programming language at Sun Microsystems Labs, which we released as open source. First Sun Labs, then Sun Microsystems itself disappeared, but because Self was open source it lived on and was later ported to run on Mac OS and Linux. My next job was in Alan Kay’s research group at Apple Computer where we created the Squeak Smalltalk system. Squeak built on Apple APDA Smalltalk (which was free but proprietary) but Ted Kaehler and Alan convinced Apple to let us release Squeak as open source. Within two weeks of its release, Squeak had been ported from Macintosh to Linux and a few weeks later to Windows. That was my first experience with the real power of an open source community. Squeak is still going strong and it also gave birth to the Pharo Smalltalk project.

My next project was Scratch, at MIT. Scratch was originally released under a custom open source license. Some people in the open source community did not like the Squeak license because it wasn’t one of the standard ones, so later versions of Squeak were released under the GPLv2 license. Squeak now has many contributors and makes use of open source software from Google and others.

After working on Scratch for 11 years, I got the itch to create another blocks language, so I left the Scratch team and joined a new research lab set up by Alan Kay. I made it a condition of my hire that everything I did would be open source, and that turned out to be a good thing. After about three years that lab closed down and I was able to take the project, GP Blocks, with me to a new research lab. At the new lab, I started the MicroBlocks project – also open source – so when that lab also closed down, both GP Blocks and MicroBlocks were able to live on. At the moment I’m putting all my time into MicroBlocks, but I may one day return to the GP Blocks project, and it’s great to know that I can.

In short, every programming language system I’ve worked on has been open source. That’s fortunate, since most of them have outlived the organizations that created them. Had they been proprietary software, they would not have survived.

BR: When I was in high school an older friend of mine lent me a Red Hat CD he got from a computer magazine and I installed it in a partition on my PC. I would from then on boot to Red Hat or Slackware regularly to play around, but I’d still use a proprietary OS as my main one. When I started university my political views began to weigh more than my need to play games, so I wiped any traces of a proprietary OS from my PC and installed Debian. I’d say using a free OS through university and my first working years taught me the importance of free software. When there’s a university assignment that requires that you use proprietary software, you need to choose between giving up on your beliefs or disobeying and using alternative free tools instead.

VB: Tell me a bit about the overall history of MicroBlocks in specific – what spurred its creation? Why did you choose a free software license in releasing it?

KG: I met Bernat while we were both working for Arduino, since he had created a still-fun-to-use tool called Snap4Arduino. He introduced me to John. We both saw the value of the idea of MicroBlocks before it was even real. It provides a live, blocks-based programming environment that is very powerful for learning and debugging, but doesn’t require that the microcontroller be connected to a laptop or other processor to run the code. It’s awesome potential is why I spend the majority of my time on it these days.

Why a free software license? We all have a motive of impact > profit. When at Mozilla, I championed a grant to MicroBlocks so they could add a “web thing” library, to make it easy to connect a microcontroller device to the web (and specifically, to Mozilla’s WebThings Gateway). I think it was at that point that John and Bernat decided to use the Mozilla Public License for the project. It is permissive – free/open to commercial and non-commercial derivatives and innovation. To me, the key to successfully maintaining “ownership”, and the ability to monetize a free software project or product (that I learned by witnessing horrible legal battles between selfish businessmen while at Arduino), is protecting the trademark. Hence: https://microblocks.fun/logo.png.

JM: While attending the 2017 SIGCSE conference, I saw a presentation about the BBC micro:bit. The presenter, Sue Sentance, gave me a BBC micro:bit to take home, and I immediately started working on MicroBlocks. The following year, the small research lab I was working for lost their funding and disbanded. I decided to keep working on MicroBlocks as an independent, open source project, along with Jens Mönig (one of the GPBlocks team and also creator of the Snap! blocks language) and Bernat, whom I’d met at the 2013 Scratch conference. Way back then, Bernat had actually planted the seed that led to MicroBlocks when he told me about an educational microcontroller board that Citilab Cornellà was developing that needed a beginner-friendly programming system.

VB: Seeing that you’ve all alluded to this, how do you all conceive of the way free software philosophies might align with the social good? For example, how might that intersection play out in the field of education?

KG: Independent of software development, if we could not learn from and innovate upon the discoveries of others, human knowledge would not likely increase from one generation to the next. Education is all about learning from others. Access to a quality education is the greatest social good we can offer to our fellow humans. Free software therefore maximizes a student’s ability to leverage programming tools and techniques already built by others so they can spend more time learning even more things, while being creative and innovative.

JM: Free software is a perfect fit for education projects. The students and schools we’d most like to reach often have limited resources. When people have to pay for educational software then only wealthy schools and students can afford it, which creates a “the rich get richer” scenario.

Creations by a student using Microblocks. Photo © Citilab Cornellà Edulab, licensed CC BY-SA 4.0

On the Scratch project, I was a strong advocate for keeping Scratch free even when we were advised that in order to scale Scratch up we needed to create a revenue stream. Fortunately, the Scratch team ignored that advice. We kept Scratch free and open source and Scratch has still managed to grow to over 57 million users!

VB: Why do you feel it is important to bring free software to ‘casual programmers’ as you’re doing with MicroBlocks?

KG: We want to see the power of logical thinking and physical computing accessible to people studying and solving problems in any domain or area of expertise. Today, to collect and analyze data, most people rely on collaboration with someone else who has a degree in computer science. I’m of the opinion that anyone from citizen scientists to top university scientists and engineers would benefit from using MicroBlocks because of how easy it is to “instrument the world around you” and take programmatic action based on what you discover. The majority of people today have never programmed a microcontroller. But with MicroBlocks, anyone who is computer literate could instrument the world, and work to make it a better place for us all.

JM: There are scores of computer programming languages for experts and professional programmers yet only a few, like Scratch, that welcome beginners. That situation tends to discourage beginners. Young people who don’t already see themselves as proficient with technology, including girls, people of color, and those from working class families, are likely to be discouraged if confronted with a complex programming language as their first experience. Languages like Scratch and MicroBlocks lower the barriers to entry and make it possible for everyone to do interesting things quickly, regardless of their background. Early successes build confidence and encourage the learner to take on more complex projects, resulting in a positive learning spiral.

It may surprise you to know that the first assignment in Harvard’s CS50, the first programming class for those majoring in computer science, is in Scratch. When Professor David Malan took over that class in 2007, he deliberately chose to use Scratch for the first assignment as a way to welcome beginners and “level the playing field”. In the Scratch assignment, students coming into CS50 with two years of AP Computer science have no advantage over students without that background. Within a year, the percentage of women and minority students completing the class had shot up dramatically. After the first assignment, CS50 switches to C++ and quickly becomes challenging, but that first assignment builds confidence and motivation that help students stick with the class for the rest of the semester.

VB: Seeing that this project converges in a certain sense with open educational resources (OER), what are your thoughts on the use of free software in education? Is OER something you feel is relevant to your project?

KG: Yes, open educational resources are super important. My goal is to create as many MicroBlocks examples and educational materials as I possibly can to help others learn physical computing. In order to improve education for all, we have to ensure equity of access. That is why the software is free and open source licensed, and the educational materials are free and open to access, improve, translate, etc.

JM: As mentioned earlier, we want to make educational software and learning resources available to everyone for free. All the MicroBlocks learning resources are shared under a Creative Commons BY-SA license. People are encouraged to translate, remix, and create new MicroBlocks Activity Cards and other materials and share them back to the community.

I also agree with Bernat: students should be able to “look inside” the software systems they are using. That’s a powerful way to learn and, even if most students never dig too deeply into the system, it’s empowering simply to know that they *can*.

BR: In the case of educational programming languages, I don’t think there should even be a question. How can you say your language is meant to teach programming if you don’t even let others look at the code that powers it?

VB: MicroBlocks seems to be doing very important work in the field of educational technology, yet it is only part of a greater free software ecosystem; with that said, what do you feel are the greatest areas of need for free software projects to focus on today?

KG: A successful project, like anything else, must solve a problem. Wherever there are emerging proprietary software solutions that are successfully “solving problems”, it will be important to see free software alternatives. For example, Linux is a fantastic OS resource compared to Windows and Mac OS, because you can modify it to suit your exact needs.

In general, I feel that lack of free software in innovative new areas of technology will continue to propagate a social equity imbalance, because “who has access” is often socially and culturally biased.

JM: The entire Linux ecosystem is absolutely essential. It’s vitally important that there be free and open source alternatives to the proprietary software created by large corporations so we are not entirely at their mercy. In addition, educational projects like One Laptop Per Child and the Raspberry Pi would not be possible without a rock-solid, free, open-source operating system, and Linux tools and infrastructure is key to many, if not most, open source projects.

BR: Even among free software users and advocates, there’s a tendency to use proprietary web applications out of convenience. Self-hosted alternatives do exist, but not everybody has the skill level or the time to deploy and maintain free alternatives to popular proprietary email, videoconferencing, file sharing, calendar or office tools. I don’t know who has the resources to do that, but I often wish there was a pre-deployed online suite comprising all these tools.

VB: What do you see for the future of your project?

KG: I see MicroBlocks as eventually becoming the de-facto educational software tool used for physical computing. On the hardware side, about 15 years ago the first Arduino boards made physical computing possible and affordable, and targeted education. The latest success story is the BBC micro:bit, an even lower-cost and far more powerful board integrated with multiple sensors and actuators. Students already carry calculators to do math, why not add a programmable microcontroller with integrated sensors and actuators to create a combination “physical computing calculator”? I imagine such a device always ready to do general mathematical and physical computations, and by connecting it to the MicroBlocks IDE, one could easily program it to do more specific or complex tasks. Casual users and Makers might benefit from and use the same type of hardware as school children, whereas top scientists and industry professionals might use a far more advanced and/or sensitive platform. Experts can still use MicroBlocks software, because they can freely update it to suit their needs.

JM: My dream is that MicroBlocks will help young people to discover the joys of building things of their own design using code and electronics. I hope to reach children who might not otherwise have imagined themselves as scientists or engineers, and I want them to see that they can use technology to bring their ideas to life and perhaps to realize that they can use their newfound abilities to bring about positive change.

VB: Now, another more general question – how do you conceive of the future of free software overall? What role do you feel your project plays in the near or long-term future of free software?

KG: People who have benefited from free software tend to produce free software if they go into any field or business area that generates foundational code. MicroBlocks is one of those excellent free software tools that will inspire the next generation to produce even more free software.

BR: MicroBlocks aims to help people get started in programming. Hopefully some of these people will end up contributing to free software projects or creating their own.

JM: I hope that many students who get started in technological fields through free software will understand the value of free software and support it. Some may even decide to “give back” by donating time or money to free software projects.

VB: How can people help support your project or get involved? How can non-technical folks contribute to your project?

KG: First, we need to spread the word. We need people who can tell and/or train educators about the benefits of MicroBlocks. Next, we need help integrating physical computing projects and examples into mainstream curriculum. Project-based learning can improve outcomes in math, science, art, music, phys-ed, etc. We want domain experts across all areas to solve physical computing problems in their field using MicroBlocks, and to share their solutions as examples for others to build upon.

And of course, we welcome everyone to click the “Donate” button on the website to offer financial support to the project (it’s a tax-deductible donation).

JM: MicroBlocks is merely a tool. For it to make a difference, educators and organizations must use it to inspire young people. Our greatest need is for people who can help us bring MicroBlocks to a wider audience, by using it in their own teaching, spreading the word to others, or creating and sharing educational materials.

BR: Individuals and organizations can support us financially through the Software Freedom Conservancy. We also encourage everybody to try out MicroBlocks and submit bug reports, either at our Git repository

or by email to interest@microblocks.fun. Translation help is always welcome! There’s also a blogpost with information about how to translate MicroBlocks.Software Freedom Conservancy is in the middle of its annual fundraiser. Please help us continue our work by becoming a Supporter. Donate now and have your donation matched by a group of generous individuals who care deeply about software freedom.

A brief introduction to the Godot Engine with Juan Linietsky, Lead Developer

by on December 28, 2020

Godot is a free-and-open-source game engine that seeks to provide an accessible, common set of tools for 2D and 3D game development. Unlike its proprietary counterparts, Godot uses the MIT license, allowing creators to exercise full agency and ownership over the products of their work, letting them focus on developing unique games on a complete, free foundation. Godot provides integrated tools for developers to work on game graphics, physics, audio, and more, and can be used to deploy games to a wide range of platforms, including the desktop, mobile platforms, the web, and several game consoles.

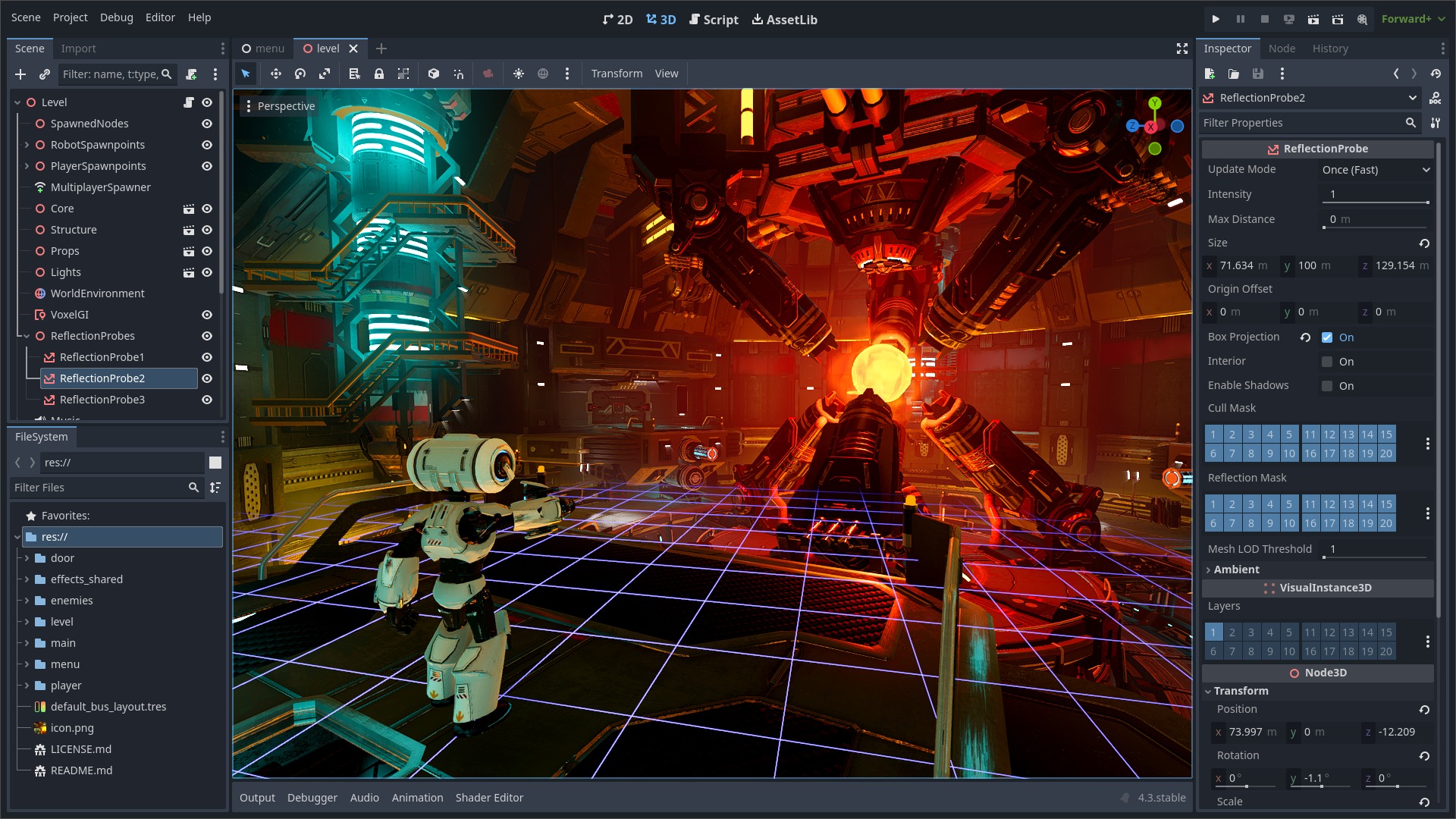

Godot demo screenshot, licensed CC BY-SA 4.0

Godot has been a Conservancy member project since 2015. Vladimir Bejdo, a Conservancy intern, conducted a remote interview with Juan Linietsky, the engine's Lead Developer, for a quick update on the work Godot is doing now five years after it joined the Conservancy and to gain some insights on the project's future.

JL: Juan Linietsky; VB: Vladimir Bejdo

VB: Juan, tell me a bit about how you got into free software to begin with – was there a particular moment or experience you could relate back to which makes free software important to you and informed this project’s libre status?

JL: I used Linux for programming since around 1997, so I was always very comfortable with free software tools. I also wrote some music composing hardware many years ago and licensed it as free software. Initially, as Godot was not meant be a commercialized product, it was put online as open source with the hopes that others would contribute.

VB: Tell me a bit about the history of the Godot Engine – what drove its creation? Why make it free software?

JL: Godot was my (and Ariel Manzur's) in-house game engine for a long time. We used it to create technology for a diverse amount of clients in the past. This was done at a time where game engines were not accessible and one needed to create the technology on your own. Because it was never meant to be a product, we open sourced it.

VB: Godot aims to provide an open, accessible, permissively licensed game engine – it would be easy to say that for many end-users and emerging developers, games are often a point of first contact with software – what kind of work does the project do to make what can often be people’s first introduction to development work accessible, and how does free software philosophy work into those aims?

JL: Godot development priorities are always very user oriented. Taking feedback from users is more important than just adding features for the sake of it. When we see users have issues with something, we try to work around it to ensure a better experience.

VB: Developing something like a game engine is somewhat of a herculean task – how has peer/community production contributed to the project’s success so far? How does the project converge with other free software projects in existence?

JL: Coexistence with other free software projects is a bit difficult. Godot does mostly not make heavy use of other open source software as a base, and instead we write our own versions of things. This is because generally we have very precise needs to solve; it's easier to roll out our own solution than doing politics with other projects to see how to work together. So, unless a library we use is exactly what we need, we tend to roll out our own. Things may take longer, but Godot becomes a lot more consistent as a result.

VB: What do you see for the future of your project as a whole?

JL: To be honest I have no idea, we are constantly running behind because it's growing so fast. I am really hoping for a time where we can work more on stabilizing the codebase and fully focusing on user experience.

VB: Would you be willing to share any use-cases of games created in Godot?

JL: Feel free to take a look at our showreel. We have lots of very beautiful looking games.

VB: Speaking more generally – what do you see for the future of free and open source software as a whole?

JL: I have mixed experiences as an open source software user myself. I am of the thinking that user experience is important when you write software, and that you should listen to your users in order to improve what you are doing. In my opinion, the biggest flaw open source software has is when the authors believe they know better than their users or other potential contributors. This hampers their ability to grow as a community. I really hope this eventually changes in the future in open source software.

VB: The Godot Engine has been a Conservancy member project for a few years now – what has changed since the Engine joined the Conservancy? How has Godot – as a project, and its community – grown over the past few years?

JL: The success of Godot as a project would have been impossible without Conservancy. The work they do to support projects in a way where they can receive donations and the way they are transparent and ensure that all funding is used for the benefit of the project is key to gaining trust with users, contributors, patrons and sponsors. It would be impossible for the project to finance itself without their help.

VB: Any closing remarks? Say someone reading this review were interested in getting involved with Godot – besides supporting the Conservancy, how might they do that?

JL: Besides thanking Conservancy again for all their help and support, I would love to invite anyone interested in taking part of the development to read our documentation page about ways to contribute.

Software Freedom Conservancy is in the middle of its annual fundraiser. Please help us continue our work by becoming a Supporter. Donate now and have your donation matched by a group of generous individuals who care deeply about software freedom.

Insights on the reproducibility and future of free software with Chris Lamb

by on December 21, 2020

The Reproducible Builds project seeks to integrate a set of development practices into software which emphasize build reproducibility, or the ability to ensure that a given build process will lead to verifiably integrous binaries which correspond to their source code. Reproducibility is especially important in software that is used for sensitive applications or even by users living in repressive regimes under mortal danger – repressive governments, for example, may choose to introduce vulnerabilities into software used by dissidents to connect to the Internet by targeting pre-compiled binaries and build processes rather than source code. The project is working towards making many widely used pieces of free software reproducible, from its aims towards making (at the very least the packages of) several widely used distributions of GNU/Linux reproducible to achieving reproducibility for individual pieces of critical software like Tor and Tails.

Participants at the 2019 Reproducible Builds Summit. Photo © intrigeri, licensed CC BY-SA 4.0

The Reproducible Builds project has been a Conservancy member project since 2018. Chris Lamb, one of the project's core team members, took part in a remote interview with Vladimir Bejdo, a Conservancy intern, to talk about the Reproducible Builds project, his own participation in software freedom, the importance of reproducibility in software development practices, and to have a discussion about the issues facing free software as a whole today – while also thinking about what issues the free software community needs to focus on going into the future.

CL: Chris Lamb; VB: Vladimir Bejdo

VB: To start off with, it might be useful to first ask you this – how would you relate the importance of reproducibility to a user who is non-technical?

CL: I sometimes use the analogy of the food ‘supply chain’ to quickly relate our work to non-technical audiences. The multiple stages of how our food reaches our plates today (such as seeding, harvesting, picking, transportation, packaging, etc.) can loosely translate to how software actually ends up on our computers, particularly in the way that if any of the steps in the multi-stage food supply chain has an issue then it quickly becomes a serious problem.

For example, even if we could guarantee that only the most wholesome apples were picked in our orchards, if they became tainted on the way to the supermarket it will be a real problem for us at the end of the day. We may not even be able to even tell by simply inspecting our Pink Ladies or Honeycrisps, and washing them thoroughly under the tap may not be enough either.

In an ideal world, we would be able to personally inspect the provenance of our food at all of the stages of manufacturing and transportation. But at some point, we must place our trust in the process and in brands, as well as various regulatory bodies to ensure that potential problems in our food are minimized, possibly even paying a time/effort premium by growing our own or buying direct from local markets in order to minimize the number of steps, etc.

However, when we use free software we can do better: ‘Reproducible builds’ are a set of software development practices, ideas and tools that create an independently-verifiable path all the way from the original source code to what actually runs on our machines. Reproducible builds can reveal the injection of back-doors introduced by the hacking of developers’ own computers, build servers and package repositories, and also expose where volunteers or companies have been coerced into making changes via blackmail, court order, and so on.

With reproducible builds, there is no longer any need to trust any particular source of authority. In the same way that, say, a Mr Smith might check that his calculator is giving him the right answer to “2+2=4” by asking enough of his friends to check theirs too, users and developers of a reproducible build can verify the software they are using by creating a collective consensus instead.

VB: Tell me a bit about how you got into free software to begin with – was there a particular moment or experience you could relate back to which makes free software important to you and informed this project’s libre status?

CL: I was playing with various Linux distributions throughout my teens, but it was only much later when I got my first permanent internet connection that I seriously got free software, intrigued by its collaborative development style, charmed by its international community and finally won over by the feelings of mastery and autonomy it gave me over my own computers. Like many others, this was only enabled by the privilege of excessive free time at a state-subsidized university. However, I first learned about ‘reproducible builds’ many years later via some friends who had attended FOSDEM in 2015.

In many ways, reproducible builds cannot be anything other than a free/libre project. As you cannot even view the source code of almost all proprietary software, the end-user benefits of having a transparent software ‘supply chain’ outside of a free software context are consequently limited. The Reproducible Builds project also brings together a broad mix of communities, philosophies and competing motivations, making it a true entrepôt of software development – it is difficult to imagine such a diverse cross-section of interests collaborating and sharing knowledge in a proprietary software context.

VB: Were there any specific grievances or moments which drove the Reproducible Build’s project’s creation?

CL: Yes and no. The idea of reproducible builds has been continually rediscovered across many eras of computing, so there have actually been a number of important moments depending on your individual perspective and biases. For example, it was implemented for various GNU tools in the early 1990s and was a property in countless systems that existed before this. None of these earlier instances resulted in mainstream developer consciousness, and all the arguments tended to forefront technical, rather than security, concerns.

However, the recent surge in interest in reproducible builds can probably be attributed to the Bitcoin project around 2011, as users of the cryptocurrency needed a way to trust that they were not downloading corrupted software. This coincided with the “Snowden” disclosures of global surveillance in 2013 and the Tor browser began serious work in this area as a direct or indirect result. These successes and a growing wider concern around software integrity prompted Debian Developer Lunar Bobbio to cultivate a sub-project within the Debian project that quickly gained popular and — crucially — technical momentum.

VB: The Reproducible Builds project works specifically on making free software work securely for sensitive targets like dissidents living in repressive states, but its work obviously also helps secure projects that are used by other at-risk populations as well. How do you feel that free software philosophies align with the social good your project tries to help foster?

CL: The Reproducible Builds project aligns with a great many of the philosophies of the free software movement. Take, for example, freedom 2 from the FSF’s “Free Software Definition”, which demands the right “to redistribute copies so you can help your neighbor”. This is admittedly not a literal application of the text, but it is difficult to reconcile the underlying intent of “helping your neighbor” if you are unwittingly distributing software that contains back-doors, and the practices and ideas of reproducible builds are intended to dramatically minimize the risk of this occurring.

In a wider sense, the concept of Reproducible Builds aligns with the general desire for autonomy and transparency present that is present throughout the free software community. This is particularly apparent in the way that it does not require people to place their trust in centralized authorities and are instead empowered to come to decisions either by themselves or collectively in a bottom-up and consensus driven manner.

VB: How has the free software community taken up reproducibility and worked to integrate it into their own development practices? Can you share with us a short overview of how the project has grown over time, or some notable implementations of the practices behind reproducible builds?

CL: There have been countless integrations of the practices of reproducible builds across the free software community, from high-level tools such as photo editors, server components such as databases, all the way down to low-level system components such as the Linux kernel (spearheaded by Ben Hutchings). Thanks to the F-Droid project, we have gained some of the benefits reproducible builds on mobile devices as well, and in 2020 we are seeing a number of independently developed Covid-19 tracing application that support being built reproducibility too.

Another prominent success story is Tails. Tails is a security-focused Linux distribution aimed at preserving privacy and anonymity. For example, it uses Tor by default and leaves no digital footprint on the internet or on the machine itself, so is ideally suited for high-risk users who face targeted or aggressive surveillance. As a result, all its systems (and engineers) that contribute to Tails’ development and release are high-priority targets for compromise as a successful attack would provide access to a large number of vulnerable and high-value users.

After considerable effort, Tails now offers fully reproducible and verifiable images, helping to protect the users of Tails but also the developers that volunteer their time to the project.

VB: What do you feel are the greatest areas of need for free software projects to focus on today overall?

CL: One area we are lacking in free software is for more robust and critical analysis of the free software movement itself.

Without greater self-reflection, we are likely to be ineffective in our approaches to real-life problem solving, and may not be able to fully realize our shared vision of a better world. For example, we might fall short and only solving problems for people we can directly relate to: everywhere on Earth, there are countless moral and ethical decisions being made around technology today, but our solutions can easily exclude others, such as those that lack technical expertise as well as those with different priorities, cultures and economic backgrounds.

As part of this critical analysis, free software projects should also not be afraid to ask what the limits or the negative externalities of developing free software might be. Even the ‘ethical consumerism’ of open source software will be inherently constrained by its very nature, yet we rarely discuss what these constraints could be. Any potential issues within our collective movement can find themselves sidelined too. For example, the potential exploitation of an unpaid, volunteer labor force of open source maintainers is not widely addressed. We also see this in the conversations around the perceived unethical co-option of free software too, where the general discourse seldom rises above unserious trading over definitions. My point is not to provide my own position here or that the free software movement should even hold any position either, but given these issue’s potential impact it seems strange and possibly even dangerous to not be widely discussing these topics, if only to assure ourselves that we are on the right path.

Likewise, if we could refine our culture of robust critique we would also be able to improve our responses to the acute and systemic problems in our society as well. For example, we might be able to comprehensively and confidently address the many harmful effects of social networks, the consolidation of power in centralized content platforms, a pervasive surveillance culture, the relegation of human agency by artificial intelligence, the role of information technology in our healthcare, the erosion of our democracy and individual freedoms, not to mention reversing or even ameliorating the effects of catastrophic climate change. The assertion that free software can help all possible situations is inspiring to me, but this optimistic hypothesis remains mostly unsubstantiated. Indeed, to all of the urgent concerns listed above, the free software movement is not yet collectively articulating a coherent and clear answer, and we can often still come across as having the same conversations regarding the name of our movement and other embarrassingly unimportant matters. Saying that, the discourse in this area has definitely been maturing in the past year or so, particularly with regard to diversity, and I am also looking forward to reading a number of pending publications in this wider area.

Given that we don’t find some topics particularly comfortable, it is only natural that we don’t tend to discuss them widely. But it is of cardinal importance that we overcome this habit: without robust and forthright self-critique, free software may actually start to contribute to society’s problems instead of diminishing them. Indeed, the twentieth-century has repeatedly demonstrated that techno-utopian and accelerationist visions of the future can just as easily lead to dystopian outcomes over positive ones however well-meaning they were when they started.

To be clear, there is absolutely nothing inherently wrong with having more application sandboxes, discussions on the finer points of funding models or even more printer drivers, but prioritizing these discussions over others may be preventing the free software movement from being taken seriously in a wider context, as well as dramatically reducing our effectiveness in solving the very real problems in our real world.

VB: Closing thoughts – how could someone begin to get involved with the project? Any resources you would like to direct readers to, if they are interested in learning more about the project and about the driving ideas behind it?

CL: If you are interested in contributing to the Reproducible Builds project, the first thing to do is connect with our community, either via our IRC channel (#reproducible-builds on irc.oftc.net) or on our mailing list.

You can also please visit the Contribute page, discover more technical details on the rest of our website, particularly via our many presentations and monthly news reports. You can also follow us on Twitter via @ReproBuilds.

Software Freedom Conservancy is in the middle of its annual fundraiser. Please help us continue our work by becoming a Supporter. Donate now and have your donation matched by a group of generous individuals who care deeply about software freedom.